A crucial brain region for behavior control is identified

There has not yet been any clear evidence of the brain areas involved in many executive functions involved in behavioral control. A new study has identified this crucial region, with the help of a unique patient and the dysexecutive syndrome.

Causal evidence was provided by a patient who had suffered several strokes

Problem-solving, planning one's own actions, controlling emotions, such executive functions are basic processes to control our behavior. Despite numerous hints, there has not yet been any clear evidence of the areas of the brain in which these abilities are processed. A study at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) has now been able to identify such a crucial region, with the help of a unique patient and the not so rare dysexecutive syndrome.

It is crucial for social and professional routines that we are able to deal with our environment and other people. Our brain’s executive functions help us with these needs. They also enable us to plan actions and divide them into individual steps that we can implement.

However, some people do not succeed in this. They find it difficult to focus, plan their actions in a goal-oriented manner, and have poor control over their impulses and emotions. They suffer from a dysexecutive syndrome, that may be triggered for example by a craniocerebral trauma or a stroke, for example.

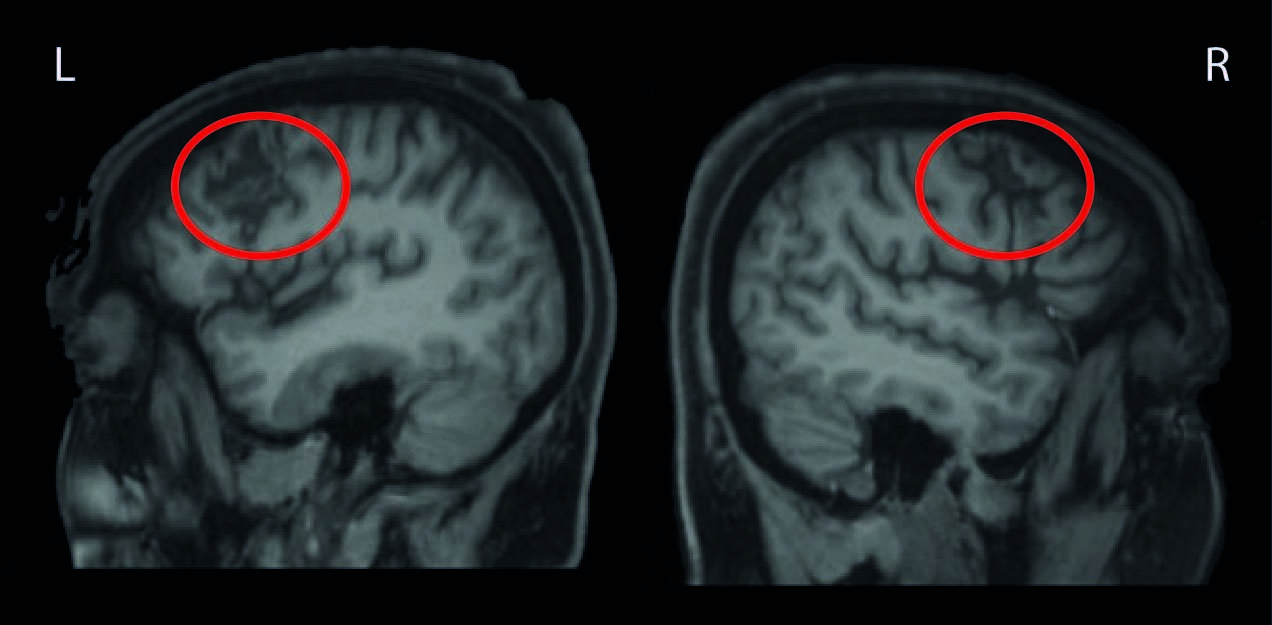

One of those affected is a 56-year-old patient from Leipzig, Germany. She had suffered several strokes that hit a strategically crucial region of the brain: The inferior frontal junction area (IFJ), located in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex in both hemispheres. Due to the injury she was no longer able to pass basic psychological tests. These included, for example, the task of planning a tour of a zoo in accordance with various guidelines, or the Stroop test (a.k.a. Stroop effect).

The patient’s lesion was confined to the inferior frontal junction region alone

The special feature of the examined patient indicated that the lesion was limited to the IFJ region alone, and equally, in both hemispheres of the brain. Normally, a stroke injures larger areas of the brain or is not restricted to such a defined area. In addition, it rarely affects the homologous areas on both sides simultaneously. As difficult as the situation is for the patient, it offers a unique opportunity for science to investigate the role of this region for executive functions.

Source: MPI CBS

"From functional MRI examinations on healthy individuals, it was already known that the IFJ region is increasingly activated when selective attention, working memory, and the other executive functions are required. However, the final proof that these executive abilities are located there has not yet been provided," explains Matthias Schroeter, the main author of the underlying study and head of the research group "Cognitive Neuropsychiatry" at the MPI CBS. However, causal evidence of such functional-anatomical relationships can only be obtained when the areas are actually switched off - and thus the abilities actually located there fail. "We have now been able to provide this with the help of the patient", Schroeter added.

Symptom reading is done through identified brain damage

In addition to the classical approach - assigning individual functions to a specific brain region on the basis of brain damage and matching to corresponding impairments - the researchers also took the opposite approach: the "big data" approach via databases. Such portals contain information from tens of thousands of participants from many psychological tests and indicate the brain areas activated in the process. With their help, the researchers were able to predict the patient's impairments based solely on the brain damage determined by the brain scans. Experts refer to this as symptom reading. A method that could be used in the future to adapt therapy to individual patients and their brain damage without having to test it in detail.

"If patients suffer from executive functions failure after an accident or stroke, for example, they are usually also less able to regenerate the other affected abilities because they have difficulty planning for them," explains Schroeter. "In the future, when the lesion images and databases provide us with more detailed information on which regions and abilities have failed, we will be able to adapt the therapy even more specifically” he explained.

Source:

Matthias L. Schroeter, Simon B. Eickhoff, and Annerose Engel, "From correlational approaches to meta-analytical symptom reading in individual patients: Bilateral lesions in the inferior frontal junction specifically cause the dysexecutive syndrome," Cortex (2020)