- There are four separate emergency numbers in France. Calls to 15 (Service d'aide médicale urgente - SAMU) are for medical emergencies only. 18 is the number for the fire department, which can also be called for medical emergencies. The number 17 takes callers to the police. Lastly, 112 calls are directed to either 15 or 18 depending on the geographic area. The idea of a single number is gradually gaining momentum. A trial in one region will begin in 2022. The fire department is in favor of this, but some emergency physicians are concerned that if the 15 number disappears, emergency services will lose their effectiveness.

The single emergency number 911 (part 1)

911 (nine-one-one) may be the best-known telephone number in the world. In the USA and Canada, these three digits are used to access emergency services of all kinds.

Birth, operation and effectiveness of 911

911 (nine-one-one) may be the best-known telephone number in the world. In the United States and Canada, these digits are used to reach emergency services of all kinds. It sounds like a simple and effective system, but it may not always be so.

Article translated from the original Italian version

This article was written by Professor Nicolas Peschanski, who practices and teaches emergency medicine in France. There, the plans to establish the European single emergency number 112 are under much debate (1). While 911 is often cited as an example by advocates of adopting a single emergency number, few people know how the system is organized. The first part of the article recounts the origins of the number 911 and describes how it works. In the second part, Prof. Peschanski focuses on the administration of medical emergencies within the 911 system and reflects on the real effectiveness of using a single emergency number in France.

"In some parts of the country, Uber arrives faster than an ambulance," said Frederick Kauser, Miffin Township Fire Chief in Ohio. "U.S. authorities estimate that up to 10,000 more lives could be saved each year by cutting 911 response times by just one minute."

These excerpts from a piece in the Wall Street Journal make us wonder.... How effective is 911?

911: One simple number, one complex process

Answering any request for help thanks to a three-digit number that is easy to remember and that may not be used for any other purpose. This simple idea was started by the National Association of Firefighters in 1957 and led to the first centers dedicated to receiving emergency calls eleven years later. The first 911 call was made in Haleyville, Alabama. In the same year, 1968, operation of 911 was validated by federal decree and its management was turned over to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Since 1972, the number has been in service in all U.S. states. Canada followed suit in 1974 with the same telephone system. It should be noted, however, that 911 covers only 97% of the geographical area of the United States and 88% of Canada's territory. Chicago as the last U.S. metropolis didn't implement 911 until 1981. Each region slowly instituted its own system. The belated Congressional formalization of 911 only in 1997 is evidence of this fragmented development.

Americans make about 240 million calls to 911 each year. These calls are handled by the roughly 8,900 Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs). When a caller dials these three numbers, they trigger a complex process that mobilizes multiple levels of decision-making and multiple people within different PSAPs that operate in different ways. At each stage, data is recorded using technologies that can vary and are more or less interconnected. There is no standard model for PSAPs, but they are divided into two categories: Primary PSAPs and Secondary PSAPs.

Primary and secondary PSAPs

A primary PSAP directly receives the call made to 911. It is the gateway to emergency services for police (police/sheriff's department), first responders (fire department) and healthcare (Emergency Medical Services, EMS). These PSAPs are usually government agencies that report to the Department of Justice or the Department of Homeland Security, that is, the police force. To give an example, New York City has five primary PSAPs. All are located in Brooklyn, but each PSAP responds to 911 calls for a different precinct.

A secondary PSAP is the center to which a 911 call can be transferred and it is most often located in a different city than the primary PSAP. With the exception of some large cities that have dedicated primary centers, only secondary PSAPs are responsible for medical emergencies. They primarily deal with these types of emergencies.

New technology: From E911 to NG911

Since 1991, the Enhanced 911 (E911) system has routed incoming calls to the appropriate PSAP based on the caller's location. That allows the operator to then view the geographic address and number of the caller. This is a system that works well with traditional landlines. However, given that cell phones accounted for more than 80% of 911 calls in 2019 and that these calls are generally associated not with a specific address, but with the area covered by the phone cell, there are two relevant issues.

First, the call may be routed to the "wrong" PSAP based on a point in the telephone cell rather than the caller's precise location. Not all PSAPs are necessarily linked to each other. The other problem is the transmission of an approximate geographic location of the caller. Under the E911 system, the telephone operator is required to transmit the caller's location with an accuracy of 50 to 300 meters. This can be problematic in the event of a premature hang-up. In fact, most police departments send officers to investigate nearby in the event of an abandoned 911 call.

The limitations of E911 prompted the emergence of Next Generation 911 (NG911). It is a digital system that allows callers to provide information through a variety of media: voice, photo, interactive video, and text message. NG911 resolves location and accessibility issues for people with hearing and speech impairments as well as those with other disabilities.

Who answers your 911 call?

The first person to respond to a 911 call is usually a law enforcement officer. Once the location has been determined and whether the situation requires more than a law enforcement response, this dispatcher then transfers the call either to a specialized dispatcher located in the primary PSAP (in the case of some large cities), or, as in most cases, to a secondary PSAP. In a medical emergency, it is this second specialist who gathers the necessary information, dispatches the EMS ambulance, and leads the securing and first aid actions at the scene.

No matter whether decisions are made by the first responder or the dispatcher, everything is conveyed verbally, but also by entering a series of priority codes and descriptions into the computer system. This specifies the desired response time and type of response.

Lack of consistency regarding codes, priorities, and deadlines

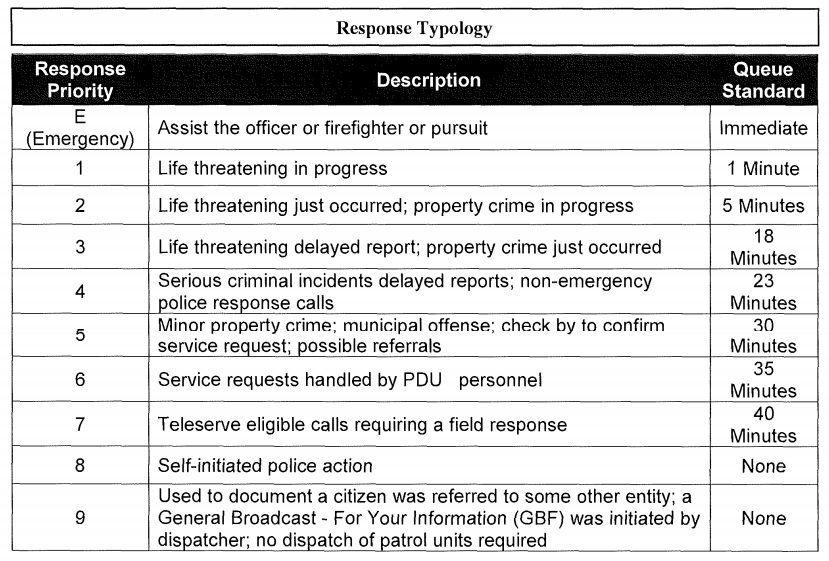

The coding system for layering and activating emergency resources is referred to as 911 dispatch codes. For example, the Houston, Texas system has 10 priority codes for calls. This system ranges from the letter "E" (highest priority, emergency vehicle response with siren wailing and blue light flashing) to the number 9 "nine" (deferrable emergency).

Houston Police Department Emergency Vehicle Dispatch Codes

This system is not consistent across the United States. Codes are collected in a guidebook published by local law enforcement agencies--and there are as many guides as there are PSAPs. However, there is a widely accepted definition of emergency calls "priority 1" (if there is reason to believe that there is an immediate threat to life) and "priority 2" (there is an immediate risk of significant loss or damage to property).

Response time

As a result of the patchwork of dispatch codes, response time targets may vary. In addition, the definition of response time targets varies in each city, county, or metropolitan area. Moreover, all response time data varies depending on the assessment methods.

In the absence of federal regulation of 911 response times, most local agencies set their own standards. The vast majority of these standards aim to have operators respond to all 911 calls within 20 seconds, with an estimated response time of 5-7 minutes for Priority 1. For Priority 2, response times range considerably across PSAPs. Average response times for some large cities are publicly available, but again there is no federal, regional, or local requirement.

Excessive use of the 911 service

The fact that the first call is taken by a law enforcement officer makes the 911 service appear generic in nature, causing people to misuse it to report incidents of any kind. In addition, the training and protocols of PSAPs can emphasize a "call center" mentality. Operators are under pressure to send agents to check in for most calls. This can have repercussions amidst a general environment of distrust and prejudice toward certain groups of the population. A report from the Vera Institute for Justice mentions 911 calls made because someone was stopped on the street or taking a nap.

In the case of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old African-American boy who was shot and killed by a police officer in 2014 while on a playground with a toy gun, 911 was notified that there was a boy "probably underage" and carrying a weapon that was "probably fake". This information did not reach the police officer, who opened fire upon arrival at the scene, even before the car he was traveling in stopped.

In an effort to relieve the 911 line of irrelevant calls, two other numbers have been established. 2-1-1 can be used to connect callers with community resources (emergency housing, veterans' services, substance abuse programs, etc.) and 3-1-1 can be used to report minor incidents (noise, graffiti, etc.).

Go to Part 2

Notes

Sources

- Riferimenti Loten A. 911 Response Times Are Getting Faster Thanks to Data Integration. The Wall Street journal. 13 juin 2019

- NENA The 9-1-1 association. https://www.nena.org/page/AboutNENA

- 911 Master PSAP Registry. https://www.fcc.gov/general/9-1-1-master-psap-registry

- Neusteter R, Mapolski M, Khogali M, O’Toole M. The 911 Call Processing System. A Review of the Literature as it Relates to Policing. Vera. July 2019

- Blackwell TH, Kaufman JS. Response time effectiveness: comparison of response time and survival in an urban emergency medical services system. Acad Emerg Med. 2002 Apr;9(4):288-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01321.x. PMID: 11927452.

- Pons PT, Haukoos JS, Bludworth W, Cribley T, Pons KA, Markovchick VJ. Paramedic response time: does it affect patient survival? Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Jul;12(7):594-600. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.013. PMID: 15995089.

- Sutter J, Panczyk M, Spaite DW, Ferrer JM, Roosa J, Dameff C, Langlais B, Murphy RA, Bobrow BJ. Telephone CPR Instructions in Emergency Dispatch Systems: Qualitative Survey of 911 Call Centers. West J Emerg Med. 2015 Sep;16(5):736-42. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.6.26058. Epub 2015 Oct 20. PMID: 26587099; PMCID: PMC4644043.

- Division of Emergency Medical Services – Public Health Seattle and King County. 2019 Annual Report

- CARES – Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival. 2017 Annual Report Greater Harris County 9-1-1 Emergency Network. https://www.911.org/resources/ghc-9-1-1-stats