- Hübschen JM, Gouandjika-Vasilache I, Dina J. Measles. Lancet. 2022 Feb 12;399(10325):678-690. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02004-3. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35093206.

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE. What's going on with measles? J Virol. 2024 Aug 20;98(8):e0075824. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00758-24. Epub 2024 Jul 23. PMID: 39041786; PMCID: PMC11334507.

- Measles cases and outbreaks. CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 23 2025.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Measles. In: ECDC. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2024. Stockholm: ECDC; 2025.

Measles: A current health issue

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases and can be dangerous in babies and young children. The best protection against measles is the vaccine.

Clinical characteristics and pathophysiology of measles

Measles is one of the most contagious viral infections known, caused by an enveloped, negative-sense single-stranded RNA virus from the genus Morbillivirus. Transmission occurs primarily via respiratory droplets and aerosols that can linger in the air for hours. The virus initially infects myeloid cells in the upper respiratory tract and disseminates through lymphoid tissues via infected lymphocytes and monocytes, resulting in systemic viremia.

Clinically, measles presents with a prodromal phase of fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, followed by the pathognomonic Koplik spots on the buccal mucosa and a descending maculopapular rash. The average incubation period is approximately 12,5 days. Patients are contagious from four days before to four days after rash onset, complicating outbreak control efforts.

Measles affects multiple organ systems and can lead to severe complications, especially in young children, immunocompromised individuals, and pregnant women. Pneumonia (either viral or due to secondary bacterial infections) accounts for most measles-related mortality. Neurologic complications include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (1 in 1.000 cases), measles inclusion body encephalitis in immunocompromised hosts, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a fatal condition occurring years after infection.

Immunological impact and vaccine-induced protection

Measles virus is notable not only for its virulence but also for its profound impact on the immune system. It induces transient but significant immune suppression, affecting both innate and adaptive responses. Dendritic cells show impaired function, and lymphocyte subsets, particularly memory B and T cells, are depleted. This immunosuppression results in increased susceptibility to other infections for up to two to three years, a phenomenon described as "immune amnesia".

Natural infection induces robust and lifelong immunity. Vaccination with live attenuated measles virus (LAMV) induces protective immunity in 90-95% of recipients after two doses, though the antibody titers and memory responses are generally less durable than those induced by wild-type infection. Vaccine-induced immunity may wane over time, with secondary vaccine failure estimated at around 5% at 10-15 years post-immunization.

Innovative vaccine strategies, including recombinant H and F protein-based vaccines, are under investigation to overcome this limitation.

Diagnostics and surveillance

Measles diagnosis is based on clinical criteria and laboratory confirmation. Detection of measles-specific IgM antibodies in serum or plasma, and RT-PCR from blood, urine, or respiratory secretions are commonly employed. Molecular diagnostics allow for early detection and genotyping, critical for tracking outbreaks and viral evolution. Although the virus is genetically stable, two wild-type genotypes (B3 and D8) continue to circulate, with some data suggesting increased transmissibility and virulence associated with genotype B3.

2025 measles outbreak in the United States

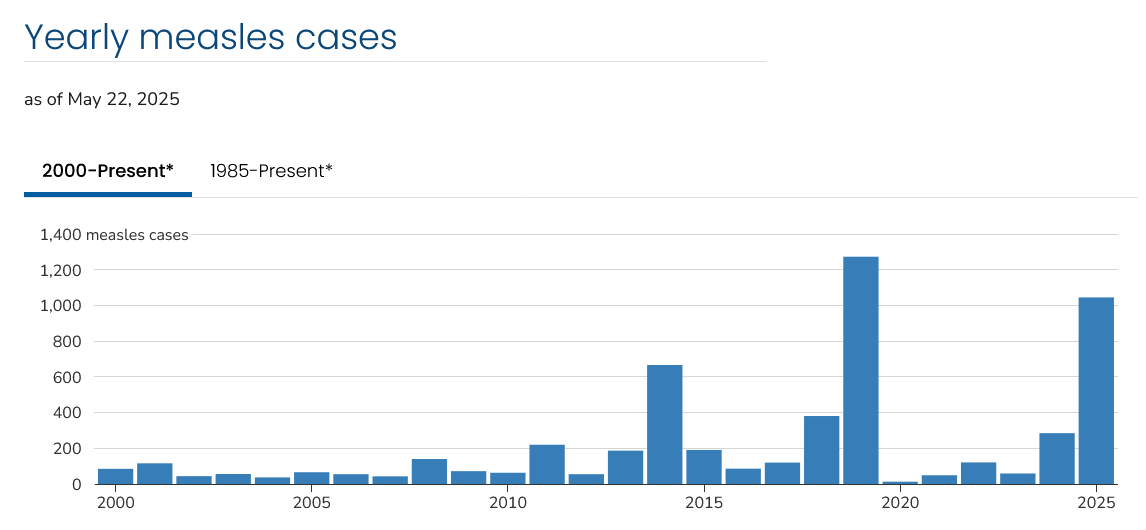

The US has experienced an unprecedented measles outbreak in 2025. As of early May, over 1.000 cases and three deaths have been reported, the highest mortality from measles in the country in decades. The outbreak originated primarily in Texas and New Mexico, with over 70% of cases concentrated in Texas. Three major clusters account for 90% of cases.

Yearly measles cases in US as of May 22, 2025 (credits: CDC)

The most affected populations include unvaccinated children and individuals with unknown vaccination status, many belonging to vaccine-hesitant communities. A significant hotspot is a Mennonite Christian community straddling Texas and New Mexico. The overall hospitalization rate is 17%. These cases mark the first measles-related deaths in the US in over a decade.

Epidemiological evidence suggests that the true case count may be underestimated due to underreporting and reluctance to seek medical care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have responded by enhancing surveillance and containment efforts. However, the outbreak has reignited debates around vaccine misinformation, especially after controversial statements by public health officials promoting unfounded concerns about vaccine safety.

The CDC recommends maintaining a 95% vaccination rate to preserve herd immunity. However, national coverage has declined from 95,2% in 2019–2020 to 92,7% in 2023–2024 among kindergarteners. The erosion of public trust in vaccination programs, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has played a key role in this regression.

This outbreak underscores the fragility of measles elimination status and the importance of sustaining high vaccination coverage, rapid outbreak response, and public health messaging rooted in scientific evidence. International cooperation is crucial, as cross-border transmission has already been documented, including cases reported in Mexico linked to the Texas outbreak.

What happens in Europe?

Although the current focus is on the US outbreak, Europe is not immune to similar risks. In 2024, a total of 35.212 measles cases were reported across the EU/EEA, marking a notable increase (ten-fold), from the 3.973 cases reported in 2023; in addition, cases reported followed a seasonal pattern, after a period (2021-23) in which the typical pattern was not evident. Measles activity had already begun to increase in 2023 after a period of unusually low activity during 2020-2022, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vaccination coverage has declined in several countries. Only 4 EU/EEA countries - Hungary, Malta, Portugal, and Slovakia - achieved the ≥95% coverage goal for the second dose of measles immunization in 2024. The upsurge is attributed to factors such as healthcare disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic and increased vaccine hesitancy.

These developments highlight the need for improved routine and catch-up immunization, enhanced surveillance, and the use of digital immunization information systems to identify undervaccinated populations. Sustained efforts are essential to prevent further outbreaks and protect vulnerable populations across Europe.