Clinical reasoning to reach a diagnosis

The clinical picture raises the issue of differential diagnosis of pneumonia associated with hypereosinophilia. The main causes to be considered in this context are listed below.

- Helminth infections: the main pathogens responsible are Ascaris (A. lumbricoides and A. suum), Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator Americanus, Toxocara Canis, Trichinella, Schistosoma and Strongyloides Stercoralis. Our patient reports no history of travel abroad in previous years. Furthermore, there is no history of exposure to domestic or wild animals, nor is there any risk of exposure to Strongyloides infestation (the patient does not have a vegetable garden and is not accustomed to frequenting wild environments). However, a direct search for parasites in faeces and respiratory secretions was performed, which was negative, as was the serology for Strongyloides Stercoralis.

- Reaction to drugs and toxins: the spectrum of iatrogenic clinical manifestations can range from asymptomatic thickening to potentially fatal conditions such as DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms). This hypothesis is not supported in this patient by her drug history, which is essentially unchanged, except for inhaled steroids, which she has been taking for years.

- Acute idiopathic pneumonia: usually follows the onset or resumption of cigarette smoking; similarly, it can result from acute exposure to chemical dusts and fumes.

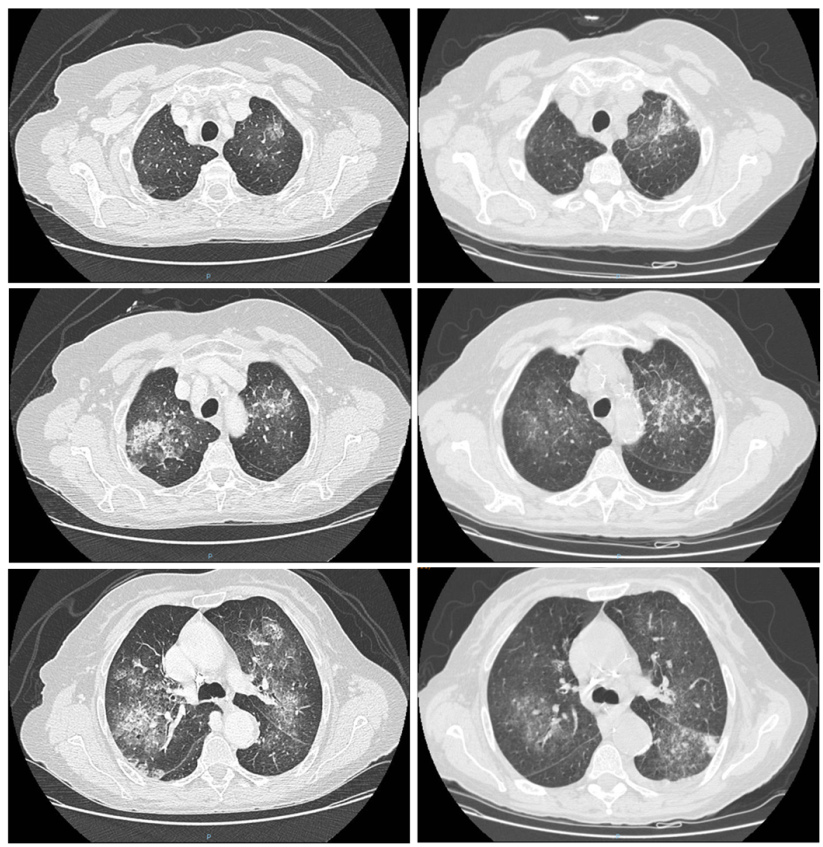

- Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: this mainly affects non-smoking women, as in this case, but usually involves mainly subpleural involvement, which is very different from that observed in the patient. It may be associated with previous radiotherapy for breast cancer.

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a complex hypersensitivity reaction resulting from exposure to Aspergillus. It usually manifests mainly in the form of chronic asthma, with frequent exacerbations. It is associated with fever, malaise, haemoptysis and peripheral eosinophilia. However, in this case too, the CT scan pattern is different, with bronchiectasis manifestations predominating, mainly affecting the apices.

- Hypereosinophilic syndromes: these are paraneoplastic, reactive or idiopathic syndromes characterised by the presence of hypereosinophilia (> 1,500 cells/µl) and potential involvement of other organs (lungs, heart, brain, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys). The clinical manifestations are caused by tissue eosinophil infiltration. The diagnosis is made in the presence of compatible clinical manifestations and hypereosinophilia, once other clinical conditions potentially responsible for the clinical picture have been ruled out.

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome): ANCA-associated vasculitis characterised by the presence of sinusitis, asthma and peripheral hypereosinophilia. Radiologically characterised by transient pulmonary opacities.

Given the clinical suspicion of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the patient underwent further tests:

- ENT evaluation: on the right side, the septal mucosa and inferior turbinate appeared to be affected by lesions suspected to be of vasculitic origin;

- P-ANCA test, which was positive at a high titre (186 IU/ml).

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, is a systemic necrotising vasculitis involving small and medium-sized blood vessels and is characterised by peripheral eosinophilia, asthma, rhinosinusitis with or without polyps, and involvement of other organs.

EGPA is classified among the so-called ANCA-associated systemic vasculitides (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies), although ANCA positivity is present in only 30-40% of patients. ANCA, generally of the p-ANCA (myeloperoxidase) variant, can help distinguish two different subsets within EGPA.

ANCA-positive EGPA patients frequently present with manifestations such as multiple mononeuritis, crescentic glomerulonephritis, and cutaneous purpura. In contrast, ANCA-negative patients more frequently present with pulmonary infiltrates, nasal polyposis, myocarditis and pleurisy. Other clinical manifestations such as systemic symptoms (fever, asthenia, arthromyalgia and weight loss) have a similar distribution in the two subtypes of EGPA. EGPA is a rare disease with one of the lowest incidence and prevalence rates compared to other systemic vasculitides.

In Europe, data from the French Vasculitis Study Group show a prevalence ranging from 10.7 to 13 cases per million inhabitants, with an incidence of 0.5-0.8 new cases per year per million inhabitants. Onset can occur at any time of life, although it is more common in adulthood, with an average age of around 50 years. Cases diagnosed in children are very rare.

The aetiology of EGPA remains unknown. It is therefore unclear what causes eosinophilic inflammation and uncontrolled activation of the immune system with a cytokine storm.

The classification criteria were revised in 2022 by the American College of Rheumatology / European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) and consist of the following:

- asthma (+ 3 points)

- nasal polyps (+ 3 points)

- multiple mononeuritis or polyneuropathy (+ 1 point)

- eosinophilia > 10% in peripheral blood (5 points)

- histological evidence of vasculitis with extravascular eosinophils (+ 2 points)

- elevated cANCA (cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) or anti-proteinase 3 antibodies (minus 3 points)

- haematuria (minus 1 point)

A score of ≥ 6 has a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99%.

Clinical course and outcome

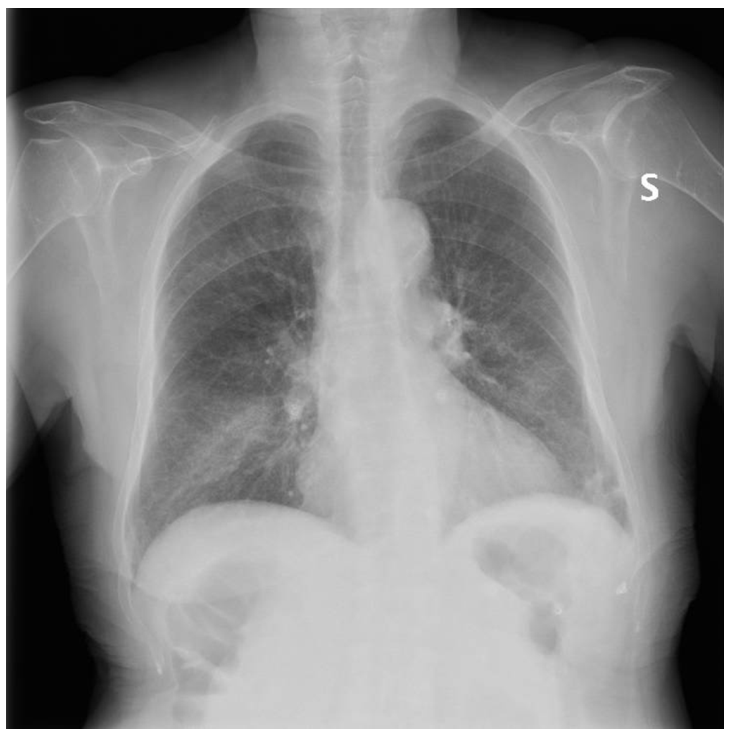

In light of the clinical picture, a diagnosis of EGPA was made. The patient presented with asthma, hypereosinophilia, transient and migratory pulmonary infiltrates, and ENT involvement (upon questioning, the patient reported chronic sinusitis). In the absence of negative prognostic factors, steroid therapy was initiated at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day of prednisone, which was subsequently combined with methotrexate.

From the first administration of steroids, a marked improvement in blood chemistry values was observed, with a complete reduction in eosinophil count, which remained persistently negative 3 months after the start of therapy. In addition, a progressive improvement in respiratory symptoms was observed, with resolution of respiratory failure.

The patient was discharged after 13 days of hospitalisation. Furthermore, after starting iron therapy, a progressive normalisation of haemoglobin values was observed. The anaemia was attributed to chronic loss from intestinal polyps, in association with a likely component attributable to the underlying chronic disorder.

- Bellan M, Delsignore E, Manfrinato C, Critto O, Barasolo G, Francese M, Olivetto L, Terribile R, Bertoncelli MC. Un caso di polmonite associata a ipereosinofilia. Federazione delle Associazioni dei Dirigenti Ospedalieri Internisti. 01 feb 2018

- Solans-Laqué R, Rúa-Figueroa I, Blanco Aparicio M, García Moguel I, Blanco R, Pérez Grimaldi F, Noblejas Mozo A, Labrador Horrillo M, Álvaro-Gracia JM, Domingo Ribas C, Espigol-Frigolé G, Sánchez-Toril López F, Ortiz Sanjuán FM, Arismendi E, Cid MC. Red flags for clinical suspicion of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Eur J Intern Med. 2024 Oct;128:45-52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2024.06.008. Epub 2024 Jun 15. PMID: 38880725.

- Emmi G, Bettiol A, Gelain E, Bajema IM, Berti A, Burns S, Cid MC, Cohen Tervaert JW, Cottin V, Durante E, Holle JU, Mahr AD, Del Pero MM, Marvisi C, Mills J, Moiseev S, Moosig F, Mukhtyar C, Neumann T, Olivotto I, Salvarani C, Seeliger B, Sinico RA, Taillé C, Terrier B, Venhoff N, Bertsias G, Guillevin L, Jayne DRW, Vaglio A. Evidence-Based Guideline for the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023 Jun;19(6):378-393. doi: 10.1038/s41584-023-00958-w. Epub 2023 May 9. PMID: 37161084.

- Chung SA, Langford CA, Maz M, Abril A, Gorelik M, Guyatt G, Archer AM, Conn DL, Full KA, Grayson PC, Ibarra MF, Imundo LF, Kim S, Merkel PA, Rhee RL, Seo P, Stone JH, Sule S, Sundel RP, Vitobaldi OI, Warner A, Byram K, Dua AB, Husainat N, James KE, Kalot MA, Lin YC, Springer JM, Turgunbaev M, Villa-Forte A, Turner AS, Mustafa RA. 2021 American College of Rheumatology / Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;73(8):1366-1383. doi: 10.1002/art.41773. Epub 2021 Jul 8. PMID: 34235894.

- Pyo JY, Lee LE, Park YB, Lee SW. Comparison of the 2022 ACR/EULAR Classification Criteria for Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis with Previous Criteria. Yonsei Med J. 2023 Jan;64(1):11-17. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2022.0435. PMID: 36579374; PMCID: PMC9826961.