Further investigations during the second examination

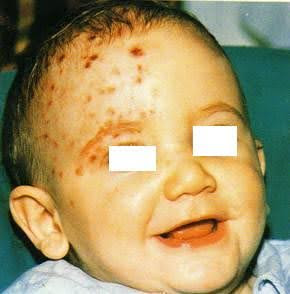

At the second examination, the lesions appear more clearly to be herpetic in nature, causing discomfort to the child, distinctly zosteriform, unilateral, dermatomal distribution affecting the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. The clinical examination suggests, contrary to all expectations given the child's age, cephalic-ophthalmic herpes zoster.

The specialists delve deeper into the medical history to distinguish between similar dermatitis conditions that could pose diagnostic doubts. In particular, the doctors ask the parents whether the child has come into contact with individuals carrying herpes simplex, also to rule out Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in atopic individuals, or contact with patients suffering from chickenpox.

Therefore, doctors recommended that the child undergo:

- an eye examination to rule out keratoconjunctivitis, which may be a symptom of a primary herpes simplex type 1 infection.

- some laboratory tests, including serology for herpes infections.

In addition, a specific high-dose antiviral therapy with acyclovir (400 mg/5 times a day), omitting the night-time dose, was prescribed for 7 days, which led to the complete resolution of the lesions. High doses for the child's age were administered, as the doctors also considered the prevention of a rare but possible keratitis and encephalitis complication.

Differential diagnosis

A. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption: negative medical history and clinical findings (lesion morphology, general signs such as diarrhoea and prostration, high fever, diffuse, disseminated, haemorrhagic vesicular lesions at the site of eczema); absence of active atopic lesions on the face.

B. Primary Herpes Simplex: apparent absence of infection from other sources, usually affecting children after the first year and before the fifth year without fever, clinical picture not exactly compatible and negative for keratoconjunctivitis and gingivostomatitis, which are the most common forms of primary herpes infection.

C. Pyoderma: as the infection progressed, the clinical picture was not suggestive and specific therapy resolved only the secondary impetiginisation, but obviously not the underlying lesions.

D. Strofulus or papular urticaria: distinguished by the presence of papular lesions, mostly on the abdomen and extensor surface of the limbs.

E. Other exanthems: the unilateral and symmetrical distribution of zoster is generally decisive.

A rare clinical case

The anamnestic and laboratory data, which according to some authors are of little use in the first months of life (anti-virus v-z immunoglobulins, present without further specifications by the laboratory, in the child's serum; anti-virus v-z IgG in the mother's serum), but above all the clinical picture, as well as the brilliant therapeutic result obtained with specific antiviral therapy, lead to a diagnosis of cephalic-ophthalmic herpes zoster, which is truly unusual for this age and which, for this reason, prevented a rapid and correct classification of the clinical case in the early days.

However, with regard to the pathogenesis of this case, some points of discussion remain open, in the sense that it is difficult to understand how the endogenous reactivation of the virus occurred, since no triggering factors have been identified, considering the hypothesis that the child had a first varicella infection transmitted to him by his mother in utero and healed here; second infection at 10 months in the form of herpes zoster.

It seems more likely that contact with patients with chickenpox transmitted the virus to the child, which, encountering a partially immunised organism, instead of causing the first infection, i.e. chickenpox, directly caused the second, i.e. herpes zoster.

HZO

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is a manifestation of herpes zoster involving the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. It occurs in approximately 4–20% of herpes zoster cases and may lead to significant ocular complications, including vision loss. Around 50% of patients with HZO develop ocular involvement—most commonly conjunctivitis, keratitis, or uveitis. HZO predominantly affects older adults: over 70% of cases occur in individuals above 50 years of age, and its incidence increases with advancing age.

Pediatric cases are extremely rare and typically associated with in utero varicella exposure or immunocompromised conditions. Early diagnosis and antiviral therapy within 72 hours are crucial to prevent complications. Recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) significantly reduces the incidence of herpes zoster and HZO in adults and is preferred over the live-attenuated vaccine. Herpes zoster in infancy is extremely rare.

In this case, the clinical picture, supported by the dramatic response to antiviral therapy, led to a diagnosis of cephalic-ophthalmic herpes zoster. However, the unusual age of onset and uncertain route of viral reactivation raise open questions about its pathogenesis, with the possibility of intrauterine transmission followed by reactivation.

- Cirfera V, Verdesca V. Un caso insolito per età. Dermatologia Legale.

- Kovacevic J, Samia AM, Shah A, Motaparthi K. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Clin Dermatol. 2024 Jul-Aug;42(4):355-359. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2024.01.007. Epub 2024 Jan 26. PMID: 38281688.

- Litt J, Cunningham AL, Arnalich-Montiel F, Parikh R. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus: Presentation, Complications, Treatment, and Prevention. Infect Dis Ther. 2024 Jul;13(7):1439-1459. doi: 10.1007/s40121-024-00990-7. Epub 2024 Jun 4. PMID: 38834857; PMCID: PMC11219696