Histology:

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with pronounced haemorrhage.

Therapy and progression:

The dermatological "visual diagnosis" follows the clearly recognisable triad of 1. "palpable purpura", 2. scattered exanthematic phenomenon and 3. "palmoplantar involvement" as well as the correlating temporal relationship of antibiotic and NSAID-treated infection.

Vasculitides are inflammatory diseases of blood vessel walls. The inconsistent classification is traditionally based on the size of the affected vessels. From a dermatological point of view, it is useful to distinguish cutaneous vasculitis with a predominant skin involvement from systemic vasculitis. Vasculitis allergica, or synonymously purpura anaphylactoid reaction, is the most common of the cutaneous vasculitides and primarily affects the small and smallest blood vessels, especially the postcapillary venules.

Etiopathologically, immune complexes are deposited on the vessel walls in the sense of an immune complex type allergy (type III according to Coombs and Gell). The inflammation with the attraction of masses of leukocytes follows an activation of the complement system. IgA antibodies are predominantly involved. The granulocytes embed themselves in the vessel wall and damage it by producing enzymes and oxygen radicals. The damage to the vessel wall at the venules leads to localised blood leaks with the development of the pathognomonic palpable purpura. In the present case, the inhibition of coagulation led to a particularly strong leakage of blood from the vessels. This is always characterised by the onset on the orthostatically stressed lower legs.

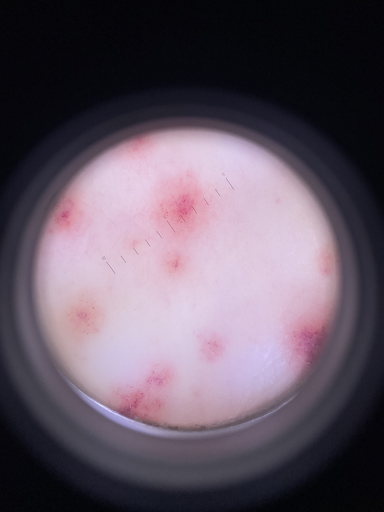

Fig. 2 shows an incipient allergic vasculitis without anticoagulation for comparison:

a

b

c

Fig. 2: In a 23-year-old female student, a purpuric exanthema had increasingly developed on the lower legs in the course of a streptogenic throat infection (a,b), and there was increasing mild pain. The non-removable punctate haemorrhages (purpura) are clearly visible in the dermatoscope (c). The connection with the bacterial infection as a carrier appears probable, although NSAIDs already taken could also be the cause.

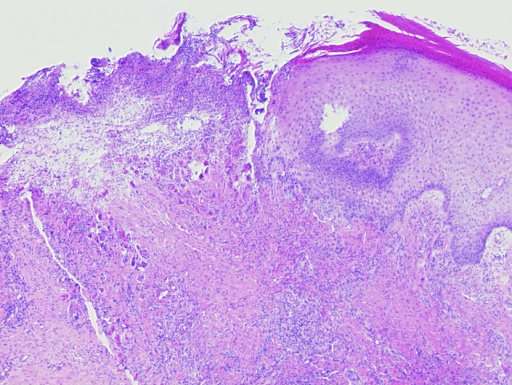

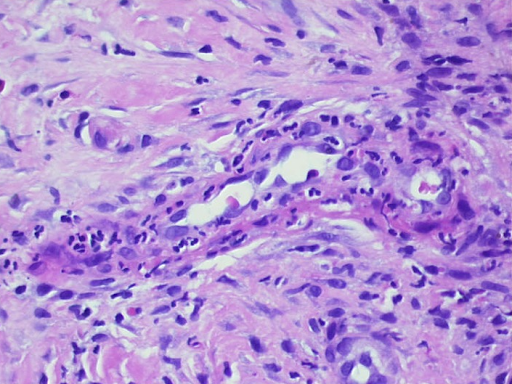

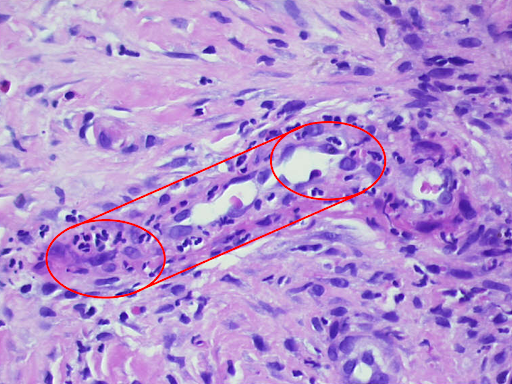

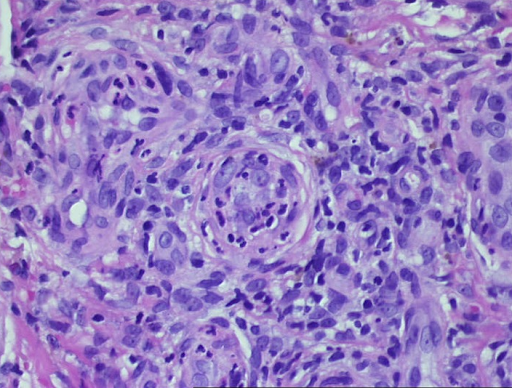

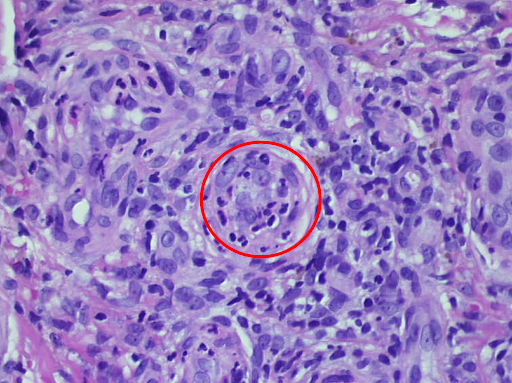

As the granulocytes involved are destroyed as they migrate through the vessel walls, this disease is also known as leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 3).

a

b

c

d

e

Fig. 3: Histological findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis at a glance, the epidermis is partially destroyed and detached, there is a massive cellular infiltrate of the dermis (a). Segmental granulocytes are found in the vessels and vessel walls. Fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls and disintegrating granulocytes, which are also deposited perivascularly (b,c). Residual obstruction and infarction of small cutaneous blood vessels (d,e).

Vascular thrombosis can lead to the development of extensive necrosis. Against a background of oral anticoagulation, as in the present case, the blood leaks are more prominent and last longer. This can lead to the development of haemorrhagic blisters. It is crucial to recognise the rapidly progressing clinical picture and to take timely therapeutic measures. Histology proves the diagnosis lege artis, but the sampling is not very pleasant for the patient and the findings report is usually only available many days later. Treatment according to clinical findings is therefore advisable.

The first step is to recognise possible trigger factors and eliminate them if possible. In acute allergic vasculitis, these may initially be respiratory (especially young patients) or urogenital infections. Bacterial antigens (e.g. streptococcal infection) and viral antigens (e.g. hepatitis A, hepatitis B) are common. On the other hand, antibiotic treatment of an infection (especially sulphonylurea preparations) or treatment with NSAIDs (salicylates) can also be the cause. Possible causes of chronic vasculitis are foreign proteins (e.g. serum sickness) or autoantigens (e.g. collagenoses, neoplasia).

In the present case, according to the medical history, cotrimoxazole was most likely the triggering agent, which was discontinued accordingly. In the case of the affected patient (Fig. 2), streptogenic triggering seemed more likely.

This distinction is important, as an antibiotic may be required in an infection-reactive situation, but a systemic steroid is more likely in the case of a drug reaction. In cases of doubt, a combination of both treatment approaches may also be appropriate. In any case, a potent steroid such as mometasone, betamethasone (class III) or clobetasol (class IV) should be applied locally in combination with lower leg compression. In severe cases, a short course of steroids starting at 1mg/kg bw and quickly tapering off may also be useful.

In the present case, the patient was hospitalised and treated with clobetasol initially and then mometasone locally for a total of 2 weeks and for 7 days with additional oral prednisolone. The treatment resulted in immediate and rapid healing, leaving behind discrete, flat scars and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. In the case of the above-mentioned student (Fig. 2), local steroid therapy and lower leg compression were sufficient for healing ad integrum. This shows the importance of rapid recognition and immediate initiation of treatment.

In chronic forms, there is good experience with systemic dapsone therapy. In general, MTX and azathioprine as well as monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab are used for severe chronic vasculitis. In young children in particular, a triad of intestinal colic, joint pain and palpable purpura on the legs should be considered as Schönlein-Henoch purpura, a special form of allergic vasculitis. The prognosis here is usually determined by immune complex nephritis. In addition to cutaneous vasculitis symptoms, there is also abdominal pain, joint and flank pain and a significantly reduced general condition. Bloody diarrhoea, haematuria and gelcaemia due to extravasation are typical of more severe cases. The urine status including albumin and the kidney values including the GFR should always be checked. Triggers are usually bacterial and viral infections 1 to 3 weeks previously. If left untreated, extreme cases can lead to acral necrosis of the limbs and even lethal progression.

Conclusion: Dermatological emergency due to vasculitis allergica

Allergic vasculitis is a dermatological emergency. It is the most common form of cutaneous vasculitis. In the vast majority of cases, timely diagnosis and treatment enable rapid healing with minimal residue. The most common triggers are bacterial and viral antigens, antibiotics and treatment with NSAIDs. The diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The therapeutic strategy includes the elimination of trigger factors if possible, local steroid therapy including compression treatment of the lower extremities and, in severe and chronic cases, the use of systemic steroids and other immunosuppressants. A special form of allergic vasculitis that is feared in children is Schönlein-Henoch purpura.