Medical Case: Refractory ARDS

A young patient with severe pneumonia deteriorates rapidly despite textbook therapy. ARDS progresses, lab signals diverge from expectations, and clinicians must abandon initial diagnoses.

Case presentation

Daniel K. is a 19-year-old man admitted to a secondary care hospital in southern Germany. He first presents late in the evening to a peripheral emergency department with abdominal pain, vomiting, and fever. An abdominal ultrasound shows no acute abnormalities, and he is discharged home with symptomatic treatment, given a working diagnosis of suspected viral gastroenteritis.

A week later, Daniel returns to the emergency department. This time, the clinical picture has clearly evolved. He reports persistent fever, diarrhoea, progressive shortness of breath, and left-sided pleuritic chest pain associated with productive cough and small amounts of haemoptysis. On examination, he appears acutely ill and dyspnoeic.

Daniel was born in Burkina Faso and has been living in Germany since early childhood. Two weeks before admission, he had returned from a visit to West Africa. His past medical history is largely unremarkable. He recalls recurrent epistaxis during childhood and reports mild unilateral hearing loss, but he has never been diagnosed with a chronic disease and does not take regular medications. A grandfather had tuberculosis many years earlier. He works as a manual labourer in a cement factory.

On arrival, vital signs reveal fever (38.4 °C), tachycardia, and hypoxaemia on room air. Arterial blood gas analysis on room air shows hypoxaemic respiratory failure with respiratory alkalosis (pO₂ 57 mmHg, pCO₂ 28 mmHg). Initial laboratory tests immediately raise concern: white blood cell count is severely reduced (530/µL), C-reactive protein is markedly elevated (241 mg/L), and serum creatinine is increased (2.38 mg/dL), consistent with acute kidney injury. Given the recent travel history to West Africa, malaria was actively investigated. Both peripheral blood smears and rapid antigen testing were negative. The patient also reported having taken antimalarial prophylaxis during his travel.

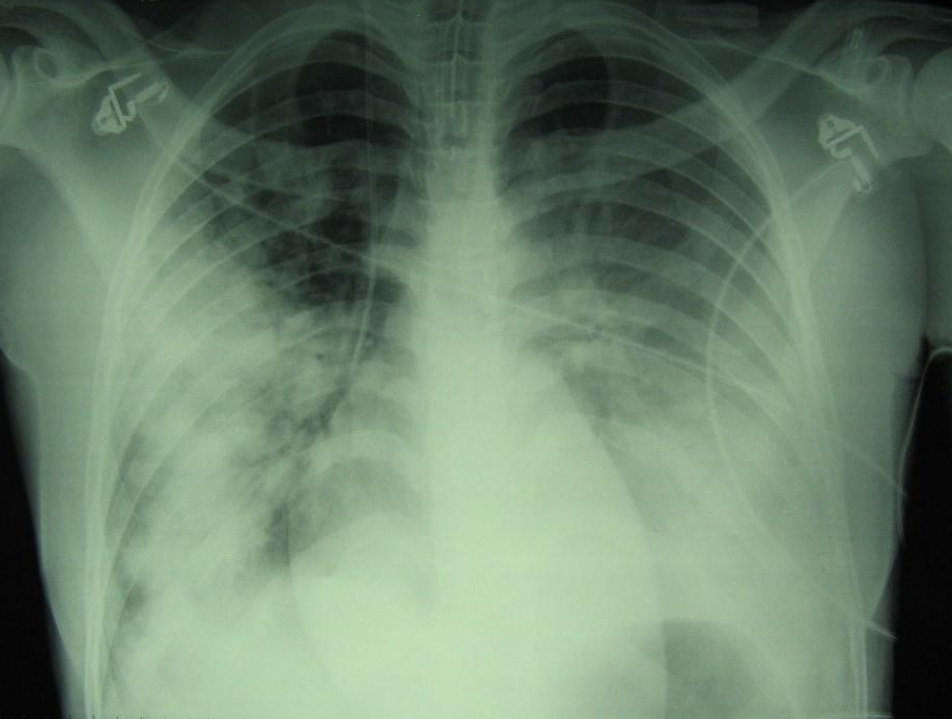

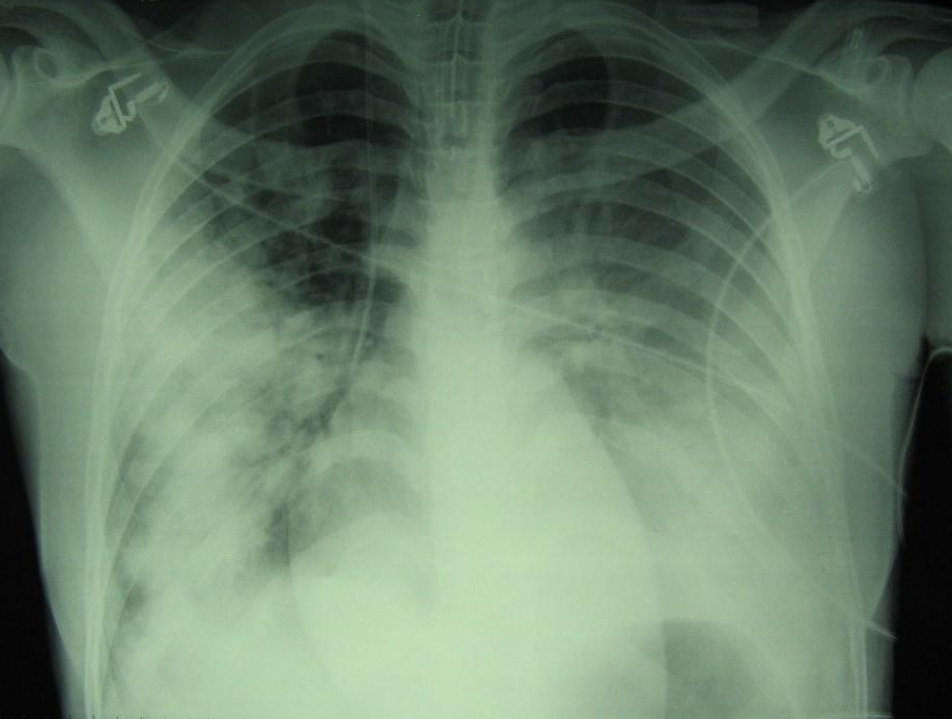

A chest X-ray reveals extensive bilateral pulmonary opacities, more pronounced on the right side, with a mixed parenchymal and pleural pattern. In the context of fever, respiratory symptoms, and radiological findings, a diagnosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia is made. Intravenous levofloxacin is started, and supplemental oxygen is administered via Venturi mask.

Chest X-ray at presentation showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, initially consistent with severe community-acquired pneumonia.

Early clinical course and escalation of care

Over the following hours, Daniel’s respiratory status deteriorates. He becomes increasingly tachypnoeic and hypoxaemic despite escalating oxygen support. Repeat arterial blood gas analysis on FiO₂ 0.5 shows persistent hypoxaemia, and haemoglobin levels fall from 15.5 g/dL to 12.6 g/dL. He is transferred overnight to the internal medicine ward of a referral hospital, described in the handover as “clinically stable but requiring close monitoring”.

By the following morning, it is evident that the situation is evolving rapidly. Daniel is tachycardic, tachypnoeic, and increasingly hypoxaemic. Lung auscultation reveals diffuse crackles bilaterally. Abdominal examination shows mild tenderness in the left flank and iliac fossa without peritoneal signs.

Repeat laboratory tests confirm persistent leucopenia, worsening inflammatory markers, and ongoing renal dysfunction. The infectious diseases team is consulted, and a comprehensive microbiological work-up is initiated, including repeated blood cultures, urinary antigens for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila, respiratory viral testing (including influenza A/H1N1), HIV serology, malaria smear and rapid test, and mycobacterial investigations.

Empirical antimicrobial therapy is broadened to include vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, levofloxacin, and oseltamivir, following a de-escalation strategy appropriate for a critically ill patient.

Within hours, Daniel’s condition deteriorates further. He develops severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure and is transferred to the intensive care unit. Despite non-invasive ventilation with high FiO₂, gas exchange continues to worsen. He requires endotracheal intubation, vasopressor support with norepinephrine, and invasive monitoring.

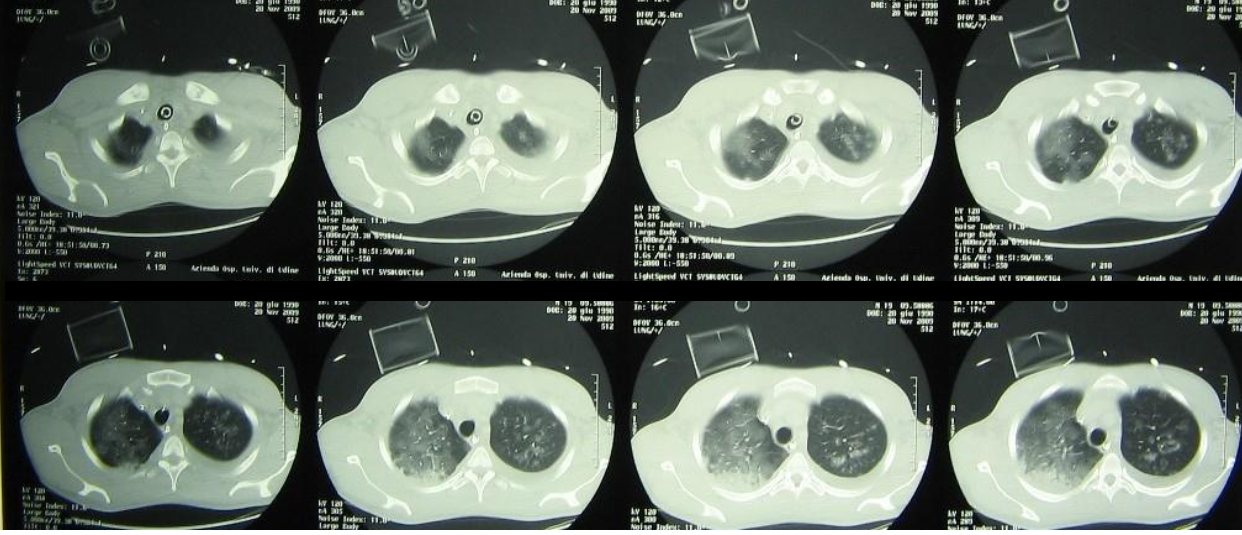

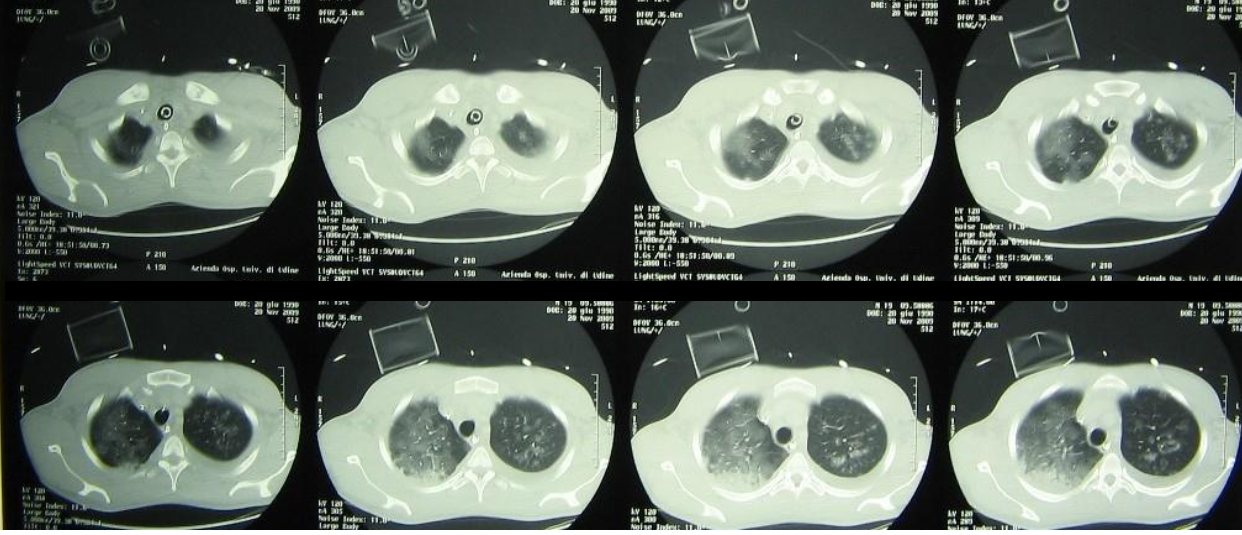

Chest imaging now shows near-complete bilateral opacification of the lungs. Echocardiography reveals global hypokinesia, more pronounced in the right ventricle, without evidence of endocarditis.

Chest CT during ICU stay showing diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidations consistent with severe ARDS.

Laboratory trends and growing diagnostic uncertainty

During the following days in the ICU, Daniel’s clinical course remains critical. Several features progressively attract the attention of the treating team.

Leucopenia persists despite supportive care, prompting haematological consultation and bone marrow aspiration, which suggests a reactive dysplastic pattern rather than primary haematological disease. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels rise steadily, exceeding 1,500 U/L. Inflammatory markers remain elevated, and gas exchange remains severely impaired despite lung-protective ventilation, pronation, and inhaled nitric oxide.

Microbiological investigations continue to yield limited results. Blood cultures remain negative. Bronchoalveolar samples are negative for bacteria, mycobacteria, and common respiratory viruses. HIV testing is repeated and remains negative. A urinary antigen test is positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae, but this isolated finding does not convincingly explain the speed, severity, and refractoriness of the clinical course.

Despite guideline-based antimicrobial therapy and maximal supportive measures, Daniel shows no meaningful improvement. He ultimately requires veno-venous ECMO due to refractory ARDS. At this stage, the initial framework of severe bacterial pneumonia no longer accounts for the overall trajectory of disease.

Correct answer: D. Opportunistic infection occurring in the setting of functional immunosuppression

By the time Daniel requires ECMO support, his illness has clearly diverged from the expected course of even severe community-acquired pneumonia. The combination of refractory ARDS, persistent leucopenia, progressive LDH elevation, and failure to respond to guideline-based antimicrobial therapy strongly suggests that bacterial infection alone cannot account for the clinical picture.

LDH elevation is a particularly relevant signal in this context. While non-specific, it is frequently associated with diffuse alveolar damage and with opportunistic infections, especially when it rises progressively in parallel with respiratory failure. Persistent bone marrow suppression further supports the presence of impaired host defences.

Although Daniel has no known history of immunodeficiency and repeated HIV testing is negative, critical illness itself can induce a state of functional immunosuppression. Severe infection, systemic inflammation, prolonged ICU stay, exposure to corticosteroids, and bone marrow dysfunction can profoundly alter immune responses, even in previously healthy individuals.

Recognising this shift in the clinical frame is essential. In such cases, strict adherence to guideline-driven algorithms may delay recognition of alternative aetiologies. Opportunistic infections - including Pneumocystis jirovecii, invasive fungal disease, parasitic hyperinfection syndromes, or viral reactivation - become plausible explanations and may justify empiric, non-conventional treatment strategies while awaiting further diagnostic clarification.

Importantly, this reasoning does not depend on a single diagnostic test but on the trajectory of disease, the accumulation of discordant clinical and laboratory findings, and the failure of conventional management.

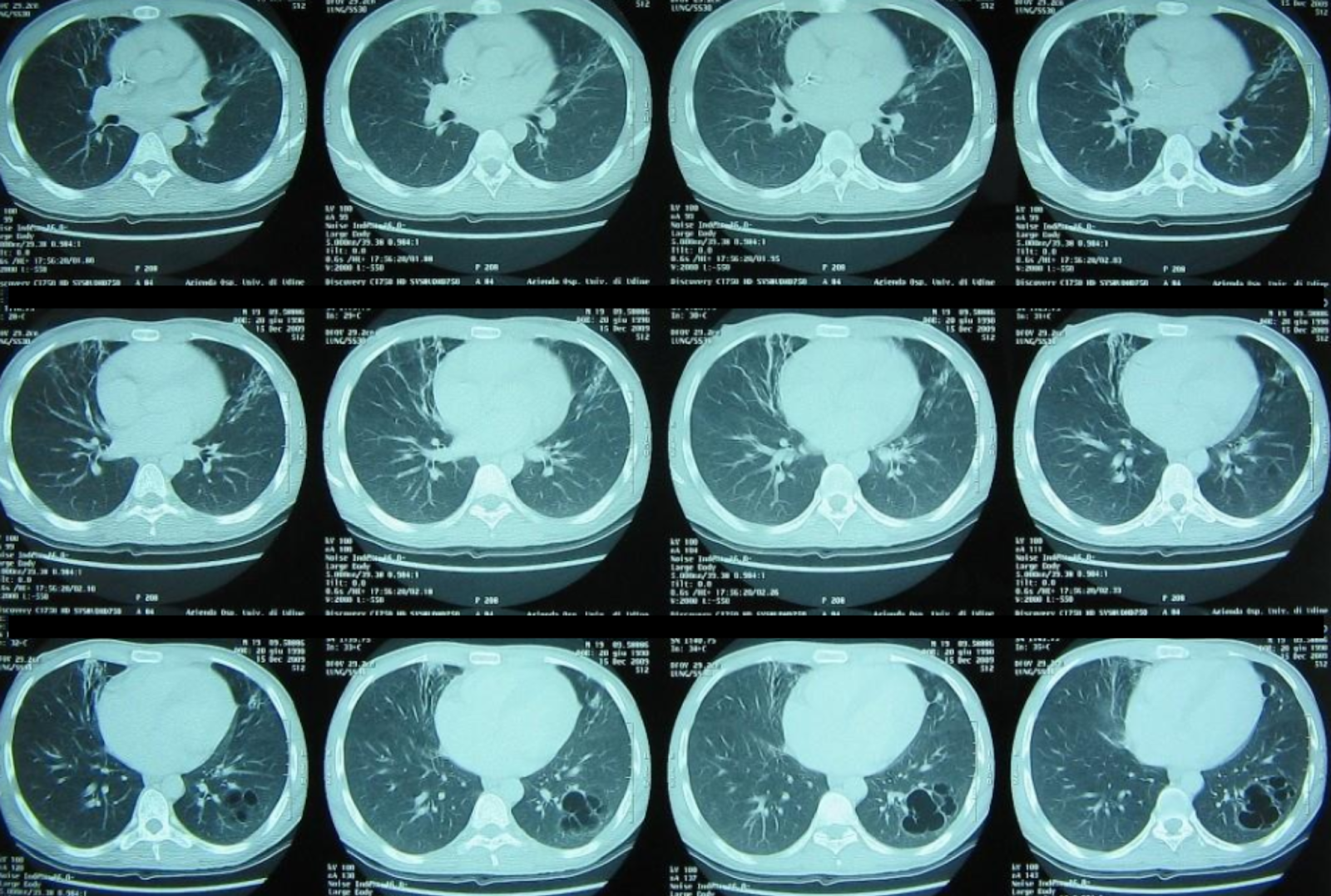

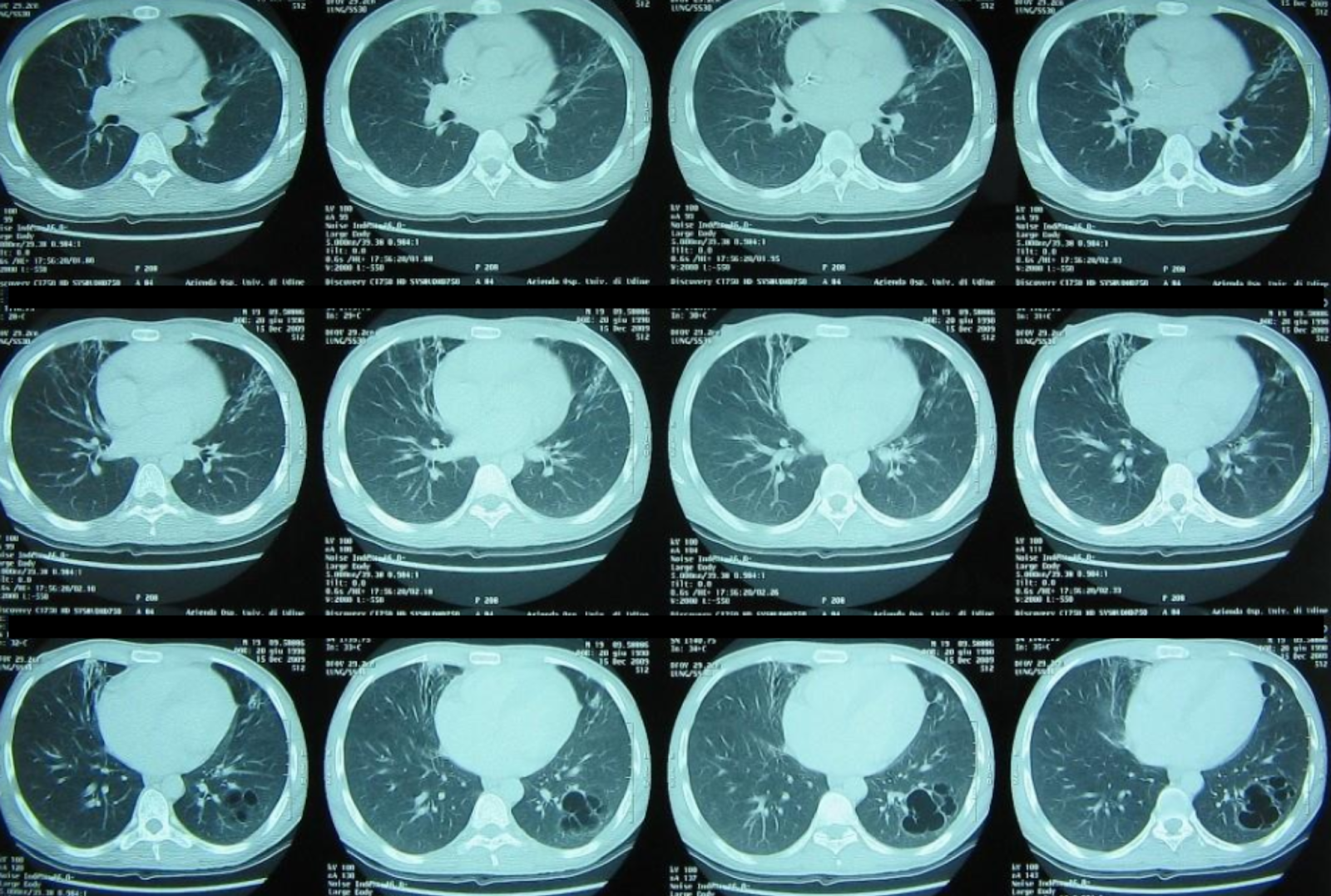

Follow-up chest CT showing partial radiological improvement following targeted non-conventional therapy.

Final diagnosis and clinical outcome

As the diagnostic work-up was further expanded in light of the patient’s refractory course, a unifying explanation finally emerged. Given Daniel’s West African origin, the early gastrointestinal symptoms preceding respiratory failure, and the precipitous progression to severe ARDS, the search for atypical and parasitic pathogens was intensified.

Stool microscopy and a repeat bronchoalveolar lavage were performed. BAL fluid analysis ultimately revealed filariform larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis, confirming a diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome.

Despite the immediate initiation of enteral ivermectin at this advanced stage of multi-organ failure, Daniel’s clinical condition remained refractory. His course was further complicated by secondary Gram-negative rod bacteremia - a classic hallmark of hyperinfection caused by larval translocation from the gut, which facilitates systemic bacterial dissemination. Progressive septic shock ensued, and despite maximal supportive care, the patient died on ICU day 12.

Post-case expert commentary

The case of Daniel K. is a sobering reminder that in the era of global migration, “latent” does not mean “absent.” Strongyloides stercoralis can persist in the human host for decades through autoinfection cycles, often remaining clinically silent.

When the delicate host–parasite equilibrium is disrupted - by critical illness, unrecognised immunosuppression, or even short courses of corticosteroids - massive larval migration may occur, leading to disseminated infection and catastrophic organ failure.

One of the key diagnostic traps in this case was the positive Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary antigen. In hyperinfection syndrome, migrating larvae can physically carry enteric bacteria on their external cuticle or within their digestive tract as they traverse from the intestine to the lungs. The resulting bacteremia may therefore represent a secondary phenomenon, masking the underlying parasitic process.

This mechanism underscores the risk of anchoring bias: the identification of a common bacterial pathogen does not exclude a more complex and dangerous aetiology, particularly when the clinical trajectory - marked by rising LDH levels, persistent leucopenia, and progressive multi-organ failure - deviates from the expected course of community-acquired pneumonia.

Key learning objectives

Recognise the gut–lung axis

In patients with epidemiological exposure to endemic areas, abdominal symptoms followed by rapidly progressive ARDS should raise suspicion for Strongyloides infection.

Interpret LDH in clinical context

Progressive LDH elevation in ARDS reflects severe parenchymal injury and should prompt consideration of opportunistic, parasitic, or non-bacterial causes.

Understand functional immunosuppression

Critical illness itself induces immune paralysis. In this setting, latent infections may reactivate and evolve into fulminant, disseminated syndromes even in previously healthy, HIV-negative individuals.