Medical History: A band of brothers

Eng and Chang were two conjoined twins scrutinised by physicians. Often described as "freaks", they made their way through conservative western America, became fathers and even landowners.

In our Medical History series, journalist Jean-Christophe Piot recounts using historical facts and story-telling, some of the most significant pages in the history of medicine.

Eng and Chang were two conjoined twins scrutinised by physicians, but they were above all, two men that lived long and rather beautiful lives. Arm in arm, these brothers, described often as "freaks", made their way through conservative western America, became fathers and even landowners.

Made in cooperation with our partners from esanum.fr

Two conjoined twin peasants who became key figures in 19th-century show business, Eng and Chang Bunker were undoubtedly among the most scrutinised personalities of their time. Not only were they closely-observed by the crowds that observed them, but also by physicians, who were fascinated by these two twins whose lives were intertwined, figuratively and physically.

August 16th, 1829. Boston, Massachusetts. From the docks, a rumour spreads like wildfire: there are two unusual passengers among those disembarking that morning from the “Sachem”, which was on a returning journey from Asia. The next morning, the curious rush to the latest edition of the city's best-informed newspaper, the Boston Patriot, confirmed the news: the capital of Massachusetts welcomed some odd visitors. They were two 17-year-old brothers, twins to be precise. But it's not the fact that they are twins that attracts the crowds’ attention, nor the respectable number of miles they have travelled from their native Siam (present-day Thailand). The curious gaze of visitors focuses elsewhere. Genetics had Eng and Chang born as joined twins, fused at the chest.

Amid the spectacle of “oddities” that was popular at the time, the Boston Patriot added a detail that would prove popular amongst their readers. For the modest sum of 50 cents, enthusiasts could contemplate this “wonder of nature” with their own eyes. A public exhibition was swiftly planned, as soon as the two brothers were examined by the most prominent members of the Boston medical community.

Eng and Chang were without a doubt already used to the curious stares that had accompanied them since as far back as they could remember. Ever since their birth in May 1811 in Meklong, a village some 80 kilometres from present-day Bangkok in what was then the Kingdom of Siam, the two brothers already attracted attention, even that of King Rama III, who welcomed them at his court in 1825.

Inseparable

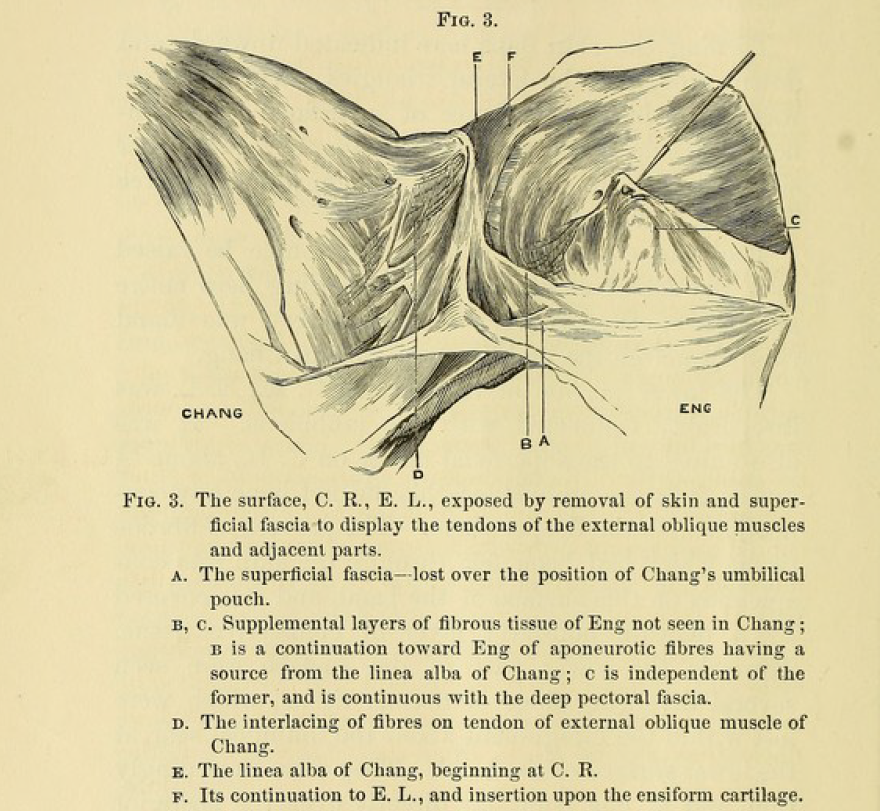

King Rama III was fascinated by the two young men, just like everyone else. And for good reason. During their mother's pregnancy, their embryos seem to have somehow merged. The twins were joined by a band of muscle and cartilage that connected them at the sternum.

But perhaps the most astonishing feature was elsewhere. Accustomed since birth to living in quasi-symbiosis, the two brothers were in good physical and psychological health. They even survived the smallpox epidemic that took the lives of several of their brothers and sisters a few years earlier. For the rest, they lived as natural a life as possible, especially since the strip of flesh that connected them was elastic enough to allow them to walk side by side without too much discomfort. The two conjoined brother twins were of short stature, and grew up as peasants like anybody else in their surroundings, helping their mother at the farm. The two children had even made a speciality of collecting and selling eggs, which they gathered from bird nests on the banks of the Mae Klong river, in Western Thailand.

It was here that Robert Hunter, a Scottish trader on a business trip, first spotted them in 1824 while the brothers were paddling bare-chested on the river. A merchant at heart, Hunter visualized a good opportunity. He quickly thought of a way to hire the twins with the idea of exhibiting them in a “freak show”, a kind of living exhibition of human or animal oddities typical of the 19th century, and which P. T. Barnum would later make one of the world's great entertainment business models. The format was simple: to charge the public for access to see what at the time were still referred to as "monsters". Dwarfs, giants, bearded women, so-called mermaids… In short, people affected by an array of mutations, diseases, or particular physical features, such as Joseph Merrick, the man who inspired David Lynch’s 1980 film The Elephant Man.

It took Robert Hunter some patience (five years in total) until in 1829 he finally convinced Chang, Eng and their mother to sign a five-year contract with him, and have them take the journey to the United States. Quite cleverly, Hunter realised that in order to seduce the public, he had to remove any doubt of the “oddity”, hence the idea of having Eng and Chang be examined by physicians in order to establish the certainty of their physical features.

The first to examine them was Dr. Joseph Skey, an Englishman sent to Boston by the British Army, closely followed by his colleague John Collins Warren, a medicine professor at Harvard. They are the first two of a very, very long list of examining medical practitioners.

Xiphopagus twins

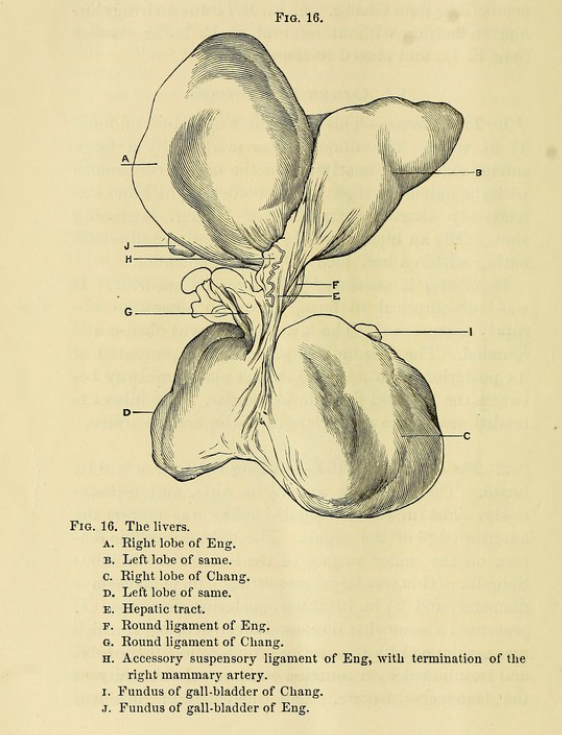

Examinations showed that at age 17 the two brothers had almost fully grown: Eng is at the time 1.57 m tall and his brother Chang is 1.56 m tall. The examining physicians took a closer look at the area where the two bodies connected. This was at the level of the sternum and the liver, which made them "xiphopagus" twins since they were united at the level of the xiphoid process, that is on the lower part of the sternum.

The clinical examination gave other interesting results. According to the reports, the two brothers did not share any common sensibility apart from this appendix of cartilage and cutaneous tissue which united them, and which appeared as a strip of skin, sufficiently elastic to allow them to walk side by side in a fluid manner - like two perfectly synchronised dancers - each one generally passing an arm around the shoulders of the brother.

Another lesson from these early tests is that they felt hungry and thirsty at the same time. Since childhood they had been eating and relieving themselves together. Their breathing and heart rates were also synchronous, at least at rest. Another point in common is that their vision was affected. They both had difficulty seeing forward, because they had to look obliquely outwards. Chang, on the other hand, is the only one who suffered from a strong spinal deviation.

A “spectacle” of burdens

Quickly introduced to the Boston public by their “impresarios”, Robert Hunter and a certain Abel Coffin, the two brothers learned English at record speed and quickly decided to spice up their performance, not wanting to just sit quietly on stage. From what was originally to be an exhibition, they turned themselves into a show designed to expose how their particularity was in no way an embarrassment. They ran, jumped, swam, played chess and performed a series of skits, acrobatics and magic tricks.

Starting in Boston, their long tour soon took them well beyond the major New England cities and made them real stars. Paid $10 and then $50 a month each, Eng and Chang left for Rhode Island and then New York, where they were again scrutinised by physicians at Rutgers Medical College. Less than six months after arriving in Boston, they set sail again for England, where half of the Royal College of Surgeons were keen to examine them.

By the end of 1830, 300,000 people had already seen them perform, including the British royal family and the exiled King of France, Charles X - one of the few Frenchmen who had the chance to see them on this tour. Initially planned, their stay in France was abruptly cancelled. The reason given: their presence could corrupt young minds exposed to an immoral and unhealthy show and disturb pregnant women. Eng and Chang saw themselves repelled from France “like monsters born of Satan", indicated the Journal des Débats in 1835 on the occasion of a new tour, this time given the green light.

The conjoined twins rebel

Between the Eng and Chang brothers, and their successive agents, the torch quickly burned. Intelligent and more educated every day, the two young men soon considered that they were largely gifted enough to manage their own careers - and to put an end to a certain amount of nonsense that irritated them, starting with the mania for dressing them up in stereotypical and cliché “Asian” fashion (meaning at the time some melange of clothing items from China) when the twins wanted to use the styles of their new homeland.

On May 11th, 1832, Eng and Chang came of age. They spent the 1830s touring on their own account in all the federal states, from Kentucky to Tennessee, passing through Alabama and Mississippi, before going on tour again abroad: Cuba, Canada, France, Holland, Belgium... Everywhere, they became a sensation, and made quite a lot of money. In October 1839, a Supreme Court decision ruled in their favour: after repeated requests, Eng and Chang were naturalised as Americans and took a new surname, Bunker. Financially comfortable but not wealthy, the two brothers decided to end their show business careers and settled in Little Sandy Creek, near Wilkesboro, North Carolina.

They became the owners of 260 hectares of good land, and had some thirty slaves. The two boys lived a luxurious life in the 1840s, typical of the planters of the Old South and of slave-owning America. By 1850, their capital was estimated at two million dollars adjusted to today’s value, which originated from their agricultural and commercial activities. The American Civil War, between 1861 and 1865, put a strain on their fortune, but the two brothers resumed their tours and were able to recover from the conflict, although without ever reaching their pre-Civil War heights. By 1870, their assets were estimated at only 600,000 dollars.

Inseparable, but not identical

Well-integrated into local society and converted to Baptist rites, the twins asserted their differences. Naturally pleasant but more reserved than his brother, Eng was an excellent chess player and a convinced militant who joined several temperance and anti-alcoholism movements, which were powerful in an America where life expectancy rarely exceeded 40 years. Smaller and more charming, but also more nervous and angry, Chang had an impetuous character. He had four or five fines for getting a reasonable number of people high during some legendary nights in the New York underworld - where he sometimes dragged his brother, of course.

While the two men occasionally quarrelled, their mutual affection never wavered. As a newspaper of the time noted, "they knew how to make life much more pleasant for each other than one might have thought", to the point of refusing the rare proposals for surgical separation. For most physicians, any attempt to separate them with a scalpel would have resulted in the death of one or both brothers.

Family lives

The most astonishing thing was not so much the ease with which the two men integrated into a deeply racist Southern society. Most intriguing was the fact that, despite this band of flesh that linked them, Eng and Chang managed to start a family. Two families, to be exact, and this time despite strong opposition from the more conservative elements of their small community. If the local papers had rumoured for some time that the two brothers aspired to get married, it was in the nature of a good joke. For racial, moral and medical reasons, such unions seemed impossible to public opinion, and most commentators felt that the twins' offspring would most certainly inherit their 'handicap'.

Yet, on April 13th, 1843, Baptist preacher Colby Sparks performed the unions of Eng and Sarah Yates on the one hand, and Chang and Adelaide Yates on the other - two sisters for two brothers. Both marriages were successful, to say the least: in just under 30 years, the couple had 21 children, none of them born with their fathers’ conditions.

Without going into the details of the Bunkers' jealously guarded intimacy, one can imagine that married life involved some special arrangements and rules. Ed and Chang lived alternately in two houses more than two kilometres apart, each turn lasting for three days. And each twin agreed to be discreet while living in his brother's house.

The twins depart

Eng and Chang experienced relatively divergent fates in the last years of their lives. In 1870, while returning from a tour of Europe interrupted by the war between France and Prussia, Chang suffered a stroke that left the right side of his body paralysed, the one that links him to his brother. Although he gradually recovered, he could no longer - they could no longer - walk up or down the stairs. Forced into retirement, the pair never left their land, with Eng taking care for years of a brother who was suffering from increasingly severe alcoholism.

On January 12th 1874 Chang started coughing and spitting. Auscultation revealed bronchial rales on the left side. Three days later, however, as usual, the twins left Chang's home for Eng's. On the evening of the 16th, Chang's chest tightness prevented the twins from lying down; they fell asleep sitting up. On the morning of January 17th, one of Eng's children noticed that his uncle Chang had died. Obviously scarred, Eng suggested that he himself would not be around much longer. Unfortunately, he is right.

For the next hour, Eng regularly asked for his legs to be moved. He asked for a urinal but his efforts to urinate were in vain. Suffocating, he lied down. Eng died two hours after the death of his twin and he remained conscious until the end.

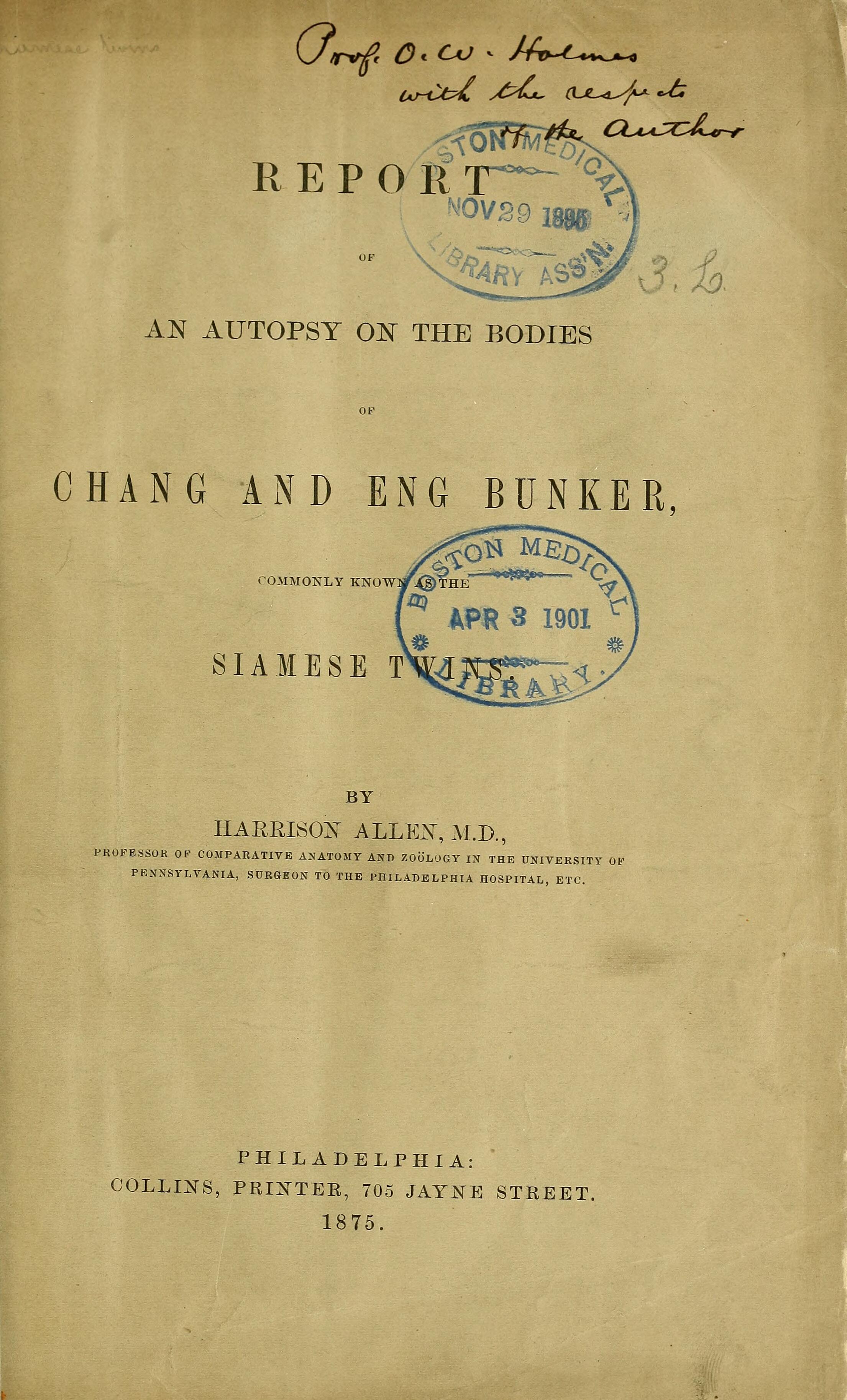

What did Eng die of? The rumour says that most likely it was the sight of his dead brother. The physicians did not reject the hypothesis. The autopsy took place "fifteen days and eight hours after death". The death report1 indicated that the weather was cool at that time while Harrisson Allen, surgeon at a Philadelphia hospital and professor of comparative anatomy, set to work on the twins bodies on February 1st, 1874.

Professor Allen’s main discovery was a hepatic connection through the cartilaginous band, where common fibres of their diaphragms were inserted. The vascular communications between the livers of the two brothers were, however, very limited and probably did not affect the functioning of their bodies during their lifetime. The peritoneal cavities and digestive systems, on the other hand, were entirely independent.

Examination confirmed the absence of heart defects. This probably explained their longevity, which is remarkable for conjoined twins. The Bunkers died at the age of 62, a venerable age for an America where the average life expectancy was only 42 years. Eng and Chang's record would not be broken until 2014, by conjoined twin brothers Ronnie and Donnie Galoon, who died in July 2020 at the age of 68.

As for their exact cause of death, the autopsy was not formal or conclusive. As the family refused to allow the brains to be examined, Professor Allen could only speculate that Chang died of cerebral venous thrombosis. The history of hemiplegia, the ante mortem pulmonary engorgement and the rapidity of death seemed to him to be valid arguments.

The surgeon was however more assertive as to the cause of Eng's death, the evidence indicated that "his bladder was severely distended and his right testicle was retracted". However, a majority of practitioners agreed that it was a blood circulation problem that killed Eng, as his circulatory system was "pumping" through the connecting strip in his dead brother's body... without receiving any blood in return.

A four-parents' household with large families, the Bunkers could boast of having had many descendants - over 1,500 at last count, according to a 2011 article in the American Journal of Medical Genetics2. Of which only 11 are twin pairs, and none of them xiphopagus.

Notes :

1. Report of an autopsy on the bodies of Chang and Eng Bunker, commonly known as the Siamese twins / by Harrison Allen

2. Conjoined Twins: A Worldwide Collaborative Epidemiological Study of the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research