A very bad "tripe" in Antarctica

1960. A physician in a remote Soviet base in Antarctica develops a very normal appendicitis. But he is not just a physician. He is THE only physician around.

In our Medical History series, journalist Jean-Christophe Piot recounts some of the most memorable episodes in medical research and events, using historical facts and story-telling.

Article translated from the original French version

Moscow, 1955

The International Geophysical Year 1957 was fast approaching. Soviet scientists were determined to play a leading role in this major international research effort aimed at better understanding the physical properties of planet Earth. Hence the Kremlin's decision to create polar bases in Antarctica and to conduct a series of studies in all fields, from geomagnetism to glaciology, meteorology and seismology.

Leningrad, 1960

Leonid Ivanovich Rogozov, a young medical intern of age 26, was preparing to interrupt his thesis on visceral surgery to join one of the six polar bases set up a few years earlier. In Rogozov’s case, it's the one at Novolazarevskaya in Queen Maud Land. Set up in the middle of nowhere, a few hundred kilometres from the coast, the station accommodated a dozen researchers.

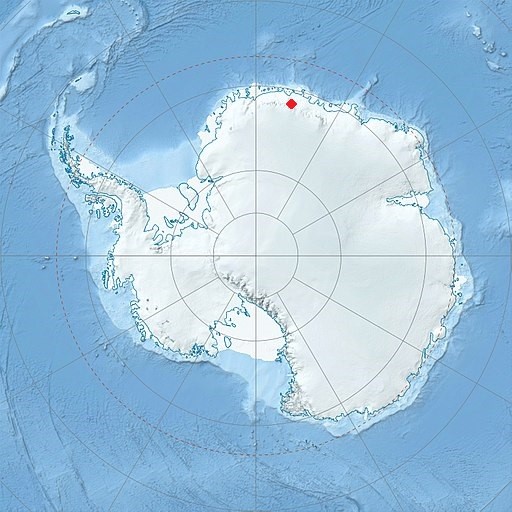

Location of the Novolazarevskaya base. Quite a ride until the next pharmacy.

When he arrived on 5th December, Rogozov quickly realised that his time there would be no picnic. With its permanent darkness and violent snowstorms, the polar winter started and cut the small group off from the rest of the world: the nearest coast line is over 2,000 kilometres away in South Africa.

The monotonous daily routine is reminiscent of life on board a submarine, where everyone plays different roles ranging from scientific research to mundane chores. As the group's only physician, Rogozov also took care of the weather surveys and occasionally acted as a driver when conditions permitted a trip. For the rest of the time, everyone did what they could and, if we’re being honest, it was probably pretty boring.

The good news is that this won't last. The bad news is that boredom can be a good thing.

"Like a hundred jackals"

On 29 April 1961, Rogozov began to feel nauseous. His temperature rose and a distinctive pain built up in his lower abdomen – on the right side. Trained as a visceral surgeon, he didn’t need to rack his brains for long: “It seems that I have appendicitis,” he wrote in his diary that day. “I am calm and even smiling. Why worry, friends? Who could help me?” No one: The ship that landed them on the coast after 36 days at sea is not due to return until the following year, and there is no pilot who would be able to land on the hard ice amid a storm.

The cold packs Rogozov put on his stomach and the antibiotics he took did not change a thing. On the morning of the 30th, after a night of vomiting, the man already looked worse: “I didn't sleep at all (...). It hurt like hell! A snowstorm whipped through my soul, moaning like a hundred jackals. Still no clear symptoms that the perforation is imminent but I have a sense of foreboding.” No one around him had even a shadow of the skills needed to operate on Rogozov. The strong winds made any chance of evacuation impossible. In the absence of adequate care, there was little doubt about his fate. In his diary, the doctor came to the only possible conclusion: “The only solution is to operate on myself.”

From room to ER

The only good news in all of this is that while Rogozov's companions were about as useful as the nearby penguins when it comes to performing surgery, they were no less resourceful. Guided by the sick man who gave them directions between vomits, they converted a room in the station into a makeshift operating theatre complete with a bed, two tables and a bedside lamp for lighting. They also sterilised everything they could in an autoclave, from instruments to bed linen.

With remarkable calm, Rogozov organised the work of the crew: one comrade to pass him the instruments, another to shine light on the scene and help him check what he was doing with a mirror, and a third one as a backup, in case the other two decided to faint. On the bedside table, adrenaline syringes were ready and waiting.

Well, there's nothing left to do but…

Rogozov opted for a semi recumbent position with his right hip slightly elevated. He also decided not to wear gloves as he felt that his sense of touch would be essential for precise movements.

On the 1st of May 1961, around two o'clock in the morning, everything was set up. "My poor assistants!" the doctor would later joke. “I took a look at them at the last moment. There they were in their surgical whites, whiter than they were themselves. I was scared, too. But once I gave myself the first injection I automatically switched into surgery mode, and from then on I didn't take notice of anything else around me.”

Rogozov injected himself with a local anaesthetic and began by incising his own abdominal wall for about twelve centimetres. While not saying that he was whistling during the procedure, he did proceed as planned for about 30 minutes until he made one mistake: “when I opened the peritoneum, I injured the appendix and had to stitch it up”.

Dr Rogozov at (self) work

The haemorrhage was severe and the blood loss made Rogozov even weaker as he had to frequently sit up straight to check on what he was doing. Sweaty and exhausted, he allowed himself a few seconds every four or five minutes before finally locating his cherished appendix. And then came the little surprise: “With horror, I noticed a blackish hue at its base. This means that one more day and it would have burst.” In other words, death was almost certain.

“My heart froze and my hands felt like rubber. I thought this was going to end badly.” And yet, Rogozov regained his senses and continued with determination. Once the removal was complete, antibiotics were applied to the peritoneal cavity and a little stitching was done to close it all up, he was able to rest after an hour and 45 minutes of extraordinary surgery. This was probably the first self-surgical procedure to be performed in the middle of a polar desert without any medical assistance.

Within five days, his temperature had returned to normal. A week later, Rogozov removed the stitches from the healing wound. By mid-May, he was back at his job for almost a year, before a difficult evacuation finally took him away from the Polar Circle, which he will not remember fondly.

Soviet hero

The Kremlin obviously seized this opportunity. One thing led to another, and the surgical operation quickly turned into a propaganda campaign. Rogozov was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour, the highest distinction for a civilian. He was compared to another figure of the 1960s, Gagarin, who was also 27 years old and, like him, came from the working class. But the doctor wasn't bothered, so much so that he shunned the honours. He quickly returned to his clinic in Leningrad, a city he would never leave again.

As a young student, Leonid Rogozov had devoted his thesis to exploring new surgical methods for the treatment of oesophageal cancer. But it was lung cancer that ended up taking his life in 1990, dying after undergoing a surgical procedure.

Since his stay in the early 1960s and until his death, Leonid Ivanovich Rogozov never set foot in Antarctica again.