Ronaldo, Coca-Cola and PubMed

The recent "controversy" involving Cristiano Ronaldo and Coca-Cola, one of the sponsors of the European football championship, sets the backdrop to explore the relationship between scientific research and private funding.

Conflicts of interest can undermine scientific research funded by private sponsors

The recent "controversy" involving Cristiano Ronaldo and Coca-Cola, one of the sponsors of the European football championship, sets the backdrop to explore the relationship between scientific research and private funding.

After the Portugal-Hungary match on 14 June 2021, as soon as Cristiano Ronaldo sat in front of the press room's microphone, made a facial gesture of disappointment and moved two bottles of Coca-Cola - one of the sponsors of Euro 2020 - from the press room podium and out of the TV frame. "Agua!" the Portuguese champion, known for his health-conscious rigour, commented. Drink water, not Coca-Cola, was the clear message.

In recent years, numerous clinical studies have highlighted the health risks of carbonated soft drinks. There are risks linked to the use of certain synthetic dyes with carcinogenic potential, and others linked to their high sugar content (and ensuing increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and/or cardiovascular damage).

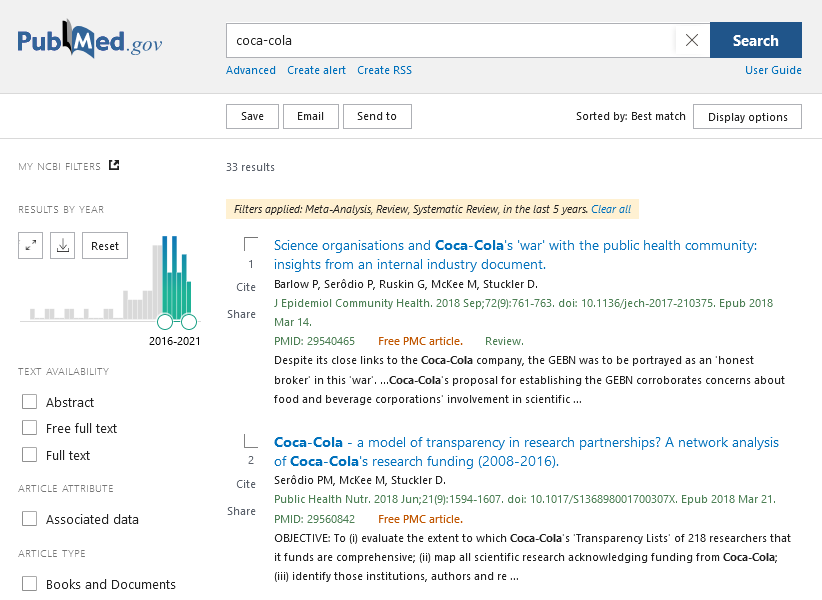

So we poked around PubMed to see if any studies had been conducted on Coca-Cola in recent years. We searched using the keyword "coca-cola" and the filters "meta-analysis", "systematic review", "review", "published in the last five years". We were struck by the first two search results on PubMed, both from 2018, which cover public health topics. We bring you the summary of the articles here, with an invitation to explore the topic further (and drink water, of course).

Coca-Cola and the war on public health

In the past years, many people thought that some food companies were working to ensure that their products were not considered to be among the causes of obesity. According to these critics, corporate action was taken by funding organisations that shifted the focus away from the discussion, highlighting different causes.

A 2018 article1 published in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health discussed how "The Coca-Cola Company" intended to further its interests by funding the Global Energy Balance Network (GEBN), a group of scholars assembled in a non-profit organisation now known to promote the idea that lack of exercise, and not poor diet, was the main culprit behind the obesity epidemic. The documents revealed that Coca-Cola had funded and supported the GEBN so that it could serve as a "weapon" to manipulate the arguments about obesity.

Despite its close ties to Coca-Cola, the GEBN was to appear as an "honest broker" in the "war" between scientific research and private enterprise. The goal of the Coca-Cola-funded GEBN was to minimise or conceal the effects of sugar on obesity. In 2020, upon news of the confirmation of the relationship between Coca-Cola and the Global Energy Balance Network2, the British Medical Journal labelled this affair as the lowest point ever reached in the history of public health3.

Coca-Cola's transparency

In 2018, a study4 assessed the list of 218 researchers funded by Coca-Cola. The list had previously been declared "transparent" by Coca-Cola itself. The analysis was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection database, retrieving all studies published between 2008 and 2016 that claimed to have received direct funding from the Coca-Cola brand. The researchers discovered the existence of 389 articles, published in 169 different journals and written by 907 researchers. Of these, Coca-Cola acknowledged funding for only 42 authors (<5%).

The researchers concluded that Coca-Cola had declared a partial list of its research activities. In addition, several funded authors appeared not to have declared funding. It was also noted that the funded research did not focus on nutrition, but emphasised the importance of physical activity and the concept of "energy balance". In practice, most of Coca-Cola's funded research was directed at supporting the importance of physical activity and neglected the role of diet in obesity.

A further noteworthy aspect of the Serôdio et al. findings, mentioned in the editorial accompanying the article5, was the inclusion of the names of the researchers as part of the study findings and discussion. The inclusion of names served to firmly ground the results, and their implications, in reality.

References:

1. Barlow P, Serôdio P, Ruskin G, McKee M, Stuckler D. Science organisations and Coca-Cola's 'war' with the public health community: insights from an internal industry document. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018 Sep;72(9):761-763. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-210375. Epub 2018 Mar 14. PMID: 29540465; PMCID: PMC6109246.

2. Serodio P, Ruskin G, McKee M, Stuckler D. Evaluating Coca-Cola's attempts to influence public health 'in their own words': analysis of Coca-Cola emails with public health academics leading the Global Energy Balance Network. Public Health Nutr. 2020 Oct;23(14):2647-2653. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020002098. Epub 2020 Aug 3. PMID: 32744984.

3. Griffin S. Coca-Cola's work with academics was a "low point in history of public health". BMJ. 2020 Aug 3;370:m3075. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3075. PMID: 32747432.

4. Serôdio PM, McKee M, Stuckler D. Coca-Cola - a model of transparency in research partnerships? A network analysis of Coca-Cola's research funding (2008-2016). Public Health Nutr. 2018 Jun;21(9):1594-1607. doi: 10.1017/S136898001700307X. Epub 2018 Mar 21. PMID: 29560842; PMCID: PMC5962884.

5. Tseng M, Barnoya J, Kruger S, Lachat C, Vandevijvere S, Villamor E. Disclosures of Coca-Cola funding: transparent or opaque? Public Health Nutr. 2018 Jun;21(9):1591-1593. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018000691. Epub 2018 Mar 21. PMID: 29560846.