SARS-Cov-2: Scientists hunt for its armour and its flaws

Researchers have identified parts of the SARS-Cov-2 viral envelope most frequently targeted by antibodies. Located on the "nails", or viral proteins, they represent a potential target for vaccine development.

Researchers have identified the parts of the SARS-Cov-2 viral envelope that are most frequently targeted by antibodies. Located on the "nails", or viral proteins, they represent a potential target for vaccine development.

Made in cooperation with our partners from esanum.fr

The Covid-19 epidemic is characterized by a wide variety of immune responses. Some people do not realize they are infected, others develop severe or even fatal forms of the illness. Swiss researchers wanted to know which antibodies are preferentially selected in people who have had Covid-19, and more importantly, at which specific locations of the SARS-Cov-2 virus they moor.

The human body continuously produces a wide variety of antibodies at random, waiting for a potential invader to attach to it and designate it as a target for the immune system to destroy. "When a new pathogen, such as SARS-Cov-2, emerges, some of these antibodies have the ability to moor to it and trigger an effective immune system response. But not everyone selects the same antibodies and therefore does not develop the same immune response," explains Nicolas Winssinger, Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Faculty of Sciences, University of Geneva (UNIGE).

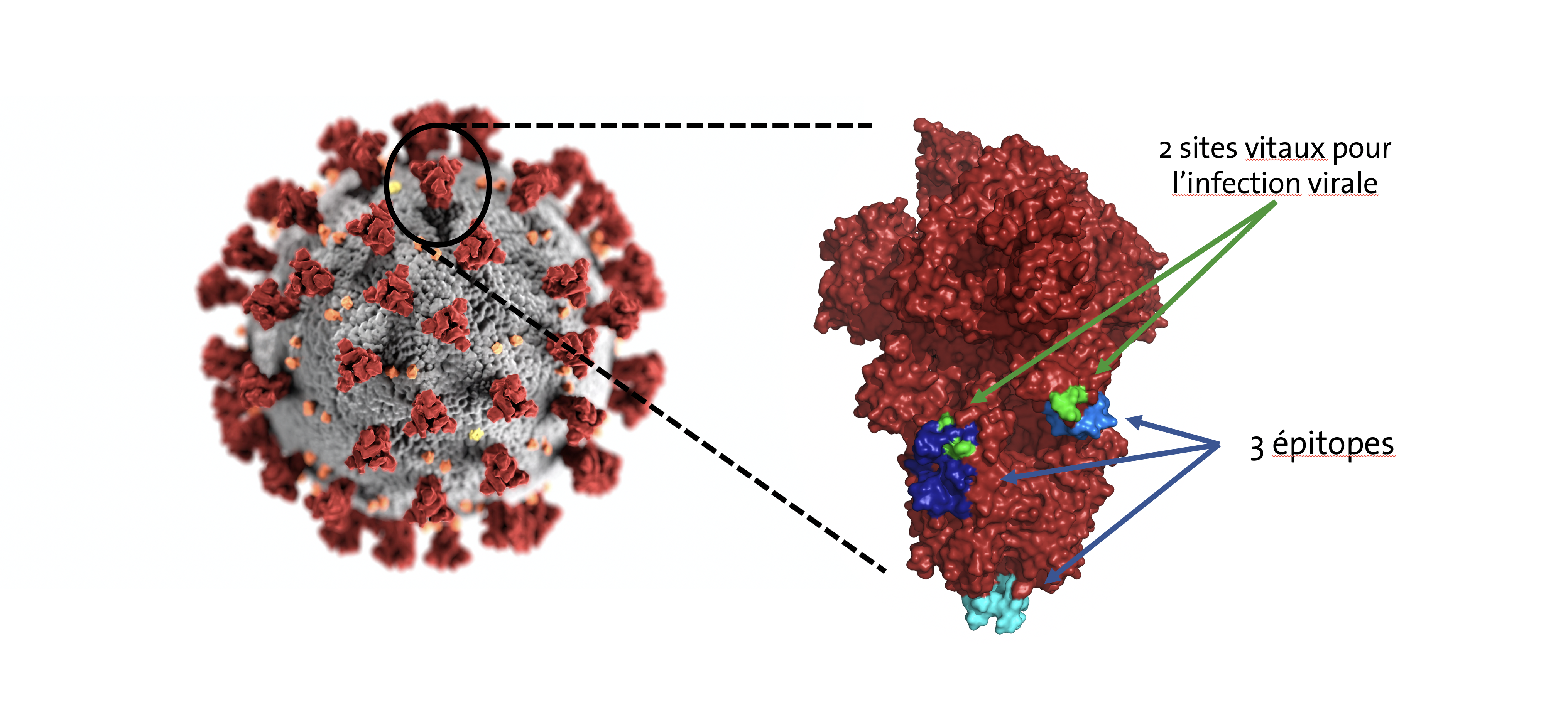

Three parts of the SARS-Cov-2 envelope are most often selected by antibodies. These targets are called "linear epitopes". However, two of them are involved in the process used by the virus to release its genetic material into human cells.

Location of the three sites most frequently targeted by human antibodies on the SARS-Cov-2 "nail". (Image credit: UNIGE)

Aim for the nail, but not its head

Results from a study of twelve Covid-19 patients confirm that these immune responses are not uniform. The only thing that all the antibodies generated by the participants have in common is that they target the "nails" - or spikes - that cover the surface of the coronaviruses. While the antibodies moor at very different locations from these large proteins, the researchers have nevertheless identified three frequently selected areas. Two of them correspond to indispensable points of attachment for proteins, the proteases, which allow the virus to fuse with the cell membrane and release its genetic material inside its prey.

"We were surprised by this result," says Nicolas Winssinger. So far, most efforts in this area have focused on the upper part of the nail, the one that is known to allow the coronavirus to attach itself to the target cell. Fusion of the virus with the cell is only the second step, but it's actually more decisive."

Indeed, attaching to a cell doesn't guarantee that the virus will be able to fuse with the cell. Furthermore, the top part of the nail may not be an ideal target for a drug or vaccine. It can even be dangerous. Studies on monkeys infected with SARS-Cov1 have shown that antibodies that attach to this area not only do not always prevent the viruses from attaching to their target cells, but also redirect them to other cell types, causing secondary diseases (antibody-dependent enhancement of diseases, ADE).

The two epitopes identified by the Geneva researchers are involved in a very different process. They could offer a promising - and less risky - alternative in the search for a new treatment or vaccine. The neutralizing power of the corresponding antibodies remains to be further looked into.