The faces and laws behind the euthanasia debate in Spain

In 1998, Ramón Sampedro ended his life aided by eleven people. By March 2021, the Spanish parliament legalised euthanasia, despite opposition from political parties, the Catholic Church, and some physicians.

A contribution from Dr. Juan Manuel Calvo Mangas

On January 12th, 1998, Ramón Sampedro ended his life with the help of eleven people. Spanish society discovered his last moments and his smiling face through a home-made video. By March 2021, the Spanish parliament legalised euthanasia, despite the fierce opposition of political parties and the Catholic Church. And the reluctance of some physicians.

Made in cooperation with our partners from esanum.fr

202 votes for, 141 against, 2 abstentions. On March 18th 2021, the Spanish Parliament ratified the law on euthanasia. Spain became the fourth European country to legalise assisted death for patients with an incurable disease, following the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. Just next door in Portugal, in late January 2021, a law decriminalising euthanasia was rejected by the Constitutional Court. Beyond Europe, Canada and New Zealand also practice euthanasia.

A sailor in hell

"Ramón Sampedro Cameán. Defensor da vida e a morte. Mariñeiro en terra. Poeta, veciño e amigo. 4-1-1943; 12-1-1998". This is the Galician language sentence stated on the plaque at the beach of As Furnas in north-east Spain, from where Ramón took a dive to the sea, with life-changing consequences. The phrase translates as “Ramón Sampedro Cameán. Defender of life and death. Sailor on land. Poet, neighbour and friend”. His accident took place in 1968, when Ramón was 25 years old. In his dive, Ramón, who had jumped head first, accidentally hit a rock, fracturing his seventh cervical vertebrae, becoming quadriplegic.

In 1998, having been a quadriplegic for almost 30 years, the former sailor Ramón Sampedro was finally able to end his life. For years he had been publicly expressing his wish to die, and had been asking the courts for permission to do so. Tired of fighting, he asked eleven anonymous people to help him. Each had a specific role, insignificant enough to prevent prosecution. One bought the potassium cyanide, another placed the glass on the bedside table, another dipped a straw in it, and so forth. Finally, Ramón's partner turned on the camera.

The video of Ramón Sampedro Cameán's last moments, with a smile on his face, deeply shocked a public opinion that was deeply divided on the issue of euthanasia. At the time, Spaniards were strongly influenced by the intransigent position of the Catholic Church. The participants of this assisted death were prosecuted. As it was not possible to establish responsibility, the courts dismissed the case.

Ramón's partner wanted to continue the legal battle he had started. In her view, the courts should have authorised Mr. Sampedro's physicians to provide him with the necessary medication to help him die with dignity. This new case was dismissed and then taken to the European Court of Human Rights, which declared the application "inadmissible".

The rest of the story took place away from the courtroom, on the big screen. Ramón, played by Javier Bardem in the 2004 Alejandro Amenabar film The Sea Inside (Spanish: Mar Adentro), caused a stir far beyond Spain. The film won a Golden Globe and then the Oscar for best foreign film.

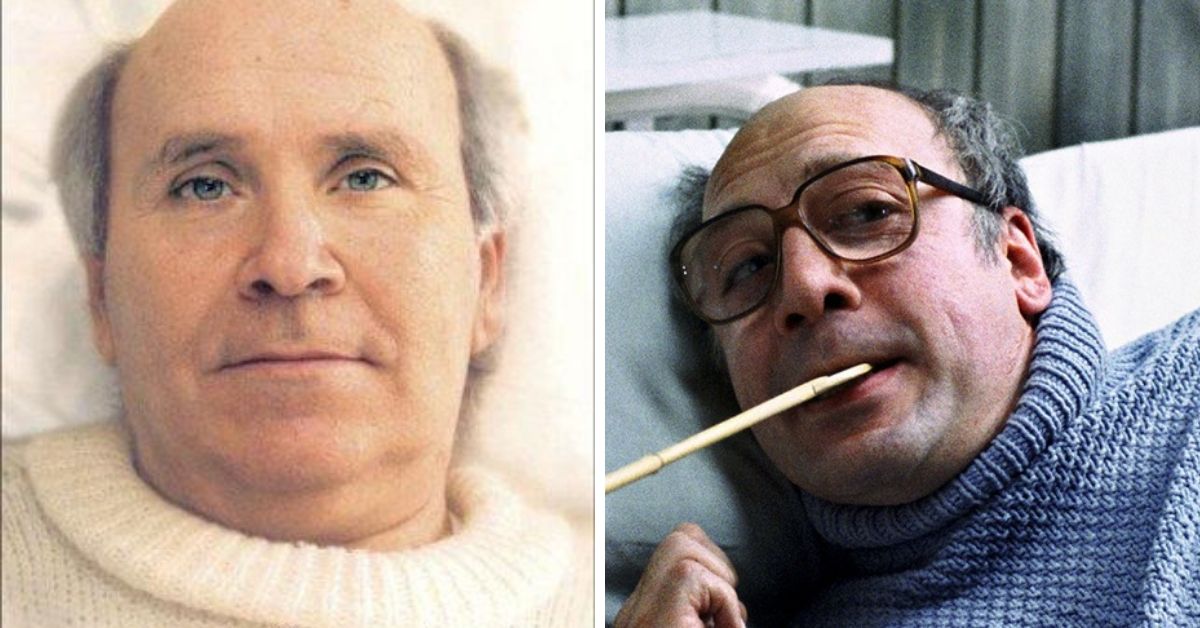

Left: Book cover of Cartas desde el Infierno (Letters from Hell) written by Ramón Sampedro and published in 1996. Right: Film still from “Mar Adentro” by Alejandro Amenábar, 2004.

Euthanasia in Spain: Strict criteria and path

More than twenty years after the death of Ramón Sampedro Cameán, a part of Spanish society has overcome its divisions on euthanasia. The new law1 will be applicable from June 25th 2021 onwards, covering "the intervention that causes the death of a person in a direct and active way, on the part of the health care personnel, by administering a substance that causes death or by prescribing it so that the person can administer it to him/herself, whether in a health centre or at home".

The context - that of an "incurable and incapacitating disease that causes intolerable suffering" - and the procedure, are very strict. The patient who opts for euthanasia will have to meet five criteria and follow a specific process:

- They must be Spanish citizens or legally resident in Spain and be of legal age, capable and conscious at the time of making the request.

- They must provide in writing all the information that exists on the patient's health problem and the different alternatives pertaining to the condition, including access to palliative care.

- The patient must make two written requests voluntarily, two weeks apart. If the patient's referring physician considers that the vital prognosis or the probable duration of the preservation of autonomy is less than this period, he or she may accept another, shorter period, which must be recorded in the patient's file.

- The patient must be a victim of a serious and incurable disease, or a serious, chronic and incapacitating disease in the terms established by law, certified by the referring physician.

- The patient must give informed consent prior to receiving the assisted termination of life. This consent must be included in the patient's file.

A patient who makes an initial request for assistance with euthanasia must therefore be informed by the physician about his or her diagnosis, therapeutic possibilities and expected prognosis, as well as the possibilities of palliative care. After confirmation by the patient and then his/her second request, the patient will meet again with the physician. The latter will then be required to consult a physician specialising in the patient's pathology, not belonging to the same care team, so that he or she can validate the request. A regional commission2 composed of seven people - physicians, paramedics and lawyers - will appoint a committee of experts to evaluate each case.

The patient will also have the possibility to draft a directive document in advance and to designate the person who will represent him/her, in case a loss of autonomy prevents him/her from confirming his/her decision later. At any time during the procedure, the physician may consider that the patient does not have sufficient autonomy or consciousness to decide. In this case, the physician must request the intervention of the expert committee. If it is later considered that this assessment of the patient has not been carried out correctly, euthanasia may be considered as assisted suicide or even homicide.

The text also requires to recognise the right of carers to conscientious objection: they will be able to refuse requests for acts that are contrary to their beliefs. The names and contact details of professionals who wish to exercise this right of conscientious objection will be recorded in an official register.

Ideological opposition and the reluctance of health professionals

This bill was not unanimously supported, quite the contrary. In parliament, it faced the opposition of the right-wing Popular Party (PP) and the far-right Vox. In civil society, it was some institutions representing carers on the one hand and the Catholic Church on the other that spoke out against the bill on several occasions throughout the approval process.

Spain’s Organización Médica Colegial, the national medical association, recalled in September 2020 that the code of ethics prohibits physicians from 'intentionally causing death, even at the express request of the patient'. In the same statement, the association argued that sedation at the end of life is ethically correct, and that physicians must avoid therapeutic overkill and respect the autonomy of patients who refuse care.

In Madrid, the regional medical association (Colegios de Médicos, Odontólogos y Farmacéuticos de Madrid) issued a statement in January 2021 calling for the withdrawal of the bill and the introduction of a General Palliative Care Act instead. The authors were highly critical of the government, which was accused of 'wanting to pass the law by decree without seeking consensus with health professionals and against the criteria of the Bioethics Committee'.

Indeed, the experts of the Spanish Bioethics Committee, an advisory body that depends on the Spanish Ministry of Health and Science, considered in a report published in September 2020 that euthanasia is not a "subjective right" and that it should not be presented as a public benefit.

On the side of the Catholic Church, opposition came from the secretary of the Conferencia Episcopal (the national Bishops' Conference). Monsignor Luis Argüello Garcia stated that "suffering cannot be avoided by provoking death". Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, President of the Roman Catholic Pontifical Academy for Life (also known as the “Pontificia Accademia per la Vita”), advocated instead for focusing on improving the quality of, and access to palliative care.

These were, quite moderate positions, when compared to the views of the Bishop of Alcalá de Henares, Monsignor Reig Pla, who wrote in a letter published the day after the vote on the euthanasia law that Spain had been transformed into an "extermination camp"3. Hardly surprising, coming from a man who had already described abortion as a "silent holocaust".

Despite the appeal to the Constitutional Court announced by the parties opposed to this law, it will come into force on June 25th, 2021. The Spanish regions therefore have three months to appoint the experts who will make up the commissions stated in the new legal framework.

Notes:

1. Ley Orgánica 3/2021, de 24 de marzo, de regulación de la eutanasia.

2. Spain has 17 autonomous communities with their own executive and legislative powers. It is a decentralised country with three levels of administration - central, regional and local - similar to those of a federal state.

3. Mons. Reig: «ESPAÑA TRANSFORMADA EN UN ''CAMPO DE EXTERMINIO''. Ante la aprobación de la ley de la Eutanasia».