Medical emergencies II: France and Louis Serre, pioneer of the SAMU

Louis Serre defined the revolutionary concept of taking the physician out of the hospital to provide care at the site of an accident and accompany the victim to the place of optimal treatment.

Revolutionising the emergency services in France

Prof. Nicolas Peschanski* granted his permission to esanum to publish this presentation provided to his students pertaining to his speciality, emergency medicine. We thank him warmly for his gesture. This is part 2 of a short series on medical emergency systems. You can check our other articles here:

Medical emergencies I: Italy and the 118 number

Medical emergencies II: France and Louis Serre, pioneer of the SAMU

Medical emergencies III: The European emergency phone number (112)

Made in cooperation with our partners from esanum.fr and esanum.it

On 1 May 1967, a call arrives at the number 72.00.00 to report a road accident in Montpellier. Within one minute, an ambulance of the Service mobile d'urgence et de réanimation de l'Hérault (Mobile Emergency and Resuscitation Service of Hérault, SMUR 34) left the Saint-Eloi hospital and went to the scene with a physician on board.

This event, which may seem banal, is in fact historic. For the first time in France, a rescue operation is "medicalised" and responds to a call received on a specially dedicated telephone number. This major advance, which consists of moving the hospital close to the victim, will revolutionise the rescue service by providing the best care in the right place at the right time. This concept, which will be adopted throughout the world, is the brainchild of a man from Montpellier with a big heart and an exceptional medical genius, Professor Louis Serre.

From 'iron lungs' to the first artificial respirators

What seems obvious today is in fact the culmination of a long story. It began with a poliomyelitis epidemic that struck Europe at the turn of the 1950s. This viral disease causes muscular paralysis which, depending on its location, can be responsible for serious respiratory problems. At the time, there were no artificial respirators. Patients suffering from respiratory failure were placed in what were called "iron lungs", a kind of chamber from which only the patient's head emerged and in which negative pressure was supposed to facilitate breathing. This only worked for mild respiratory failure. The other solution was to ventilate manually with balloons connected to a face mask, as in an operating theatre for sleeping patients.

A Swedish engineer, Carl Gunnar Engström, then developed the first real artificial respirators and France acquired a few devices. Louis Serre, a resuscitation anaesthetist in Montpellier, was asked to transport certain patients to hospitals with these respirators. For the first time in the civilian field, a physician assisted a seriously ill patient requiring respiratory assistance in an ambulance.

In the decade that followed, another "epidemic" hit France, that of road accidents. Each year, nearly 15,000 deaths and 300,000 injuries were the toll paid by the increase in the standard of living and the acquisition of vehicles that had become accessible to the majority of people. This death toll is the result of several associated factors: vehicle design, lack of seat belts and the absence of any speed limit.

But the death toll is also attributable to the fact that the treatment of road victims is totally unsuited to their condition. The fire brigades, most of them volunteers, do their best - but their first aid training is, at the very least, rudimentary. For the injured who have survived the accident, transport without any care other than a few bandages is accompanied by a thousand sufferings, in bumpy vehicles, diverted from their original purpose intended for farmers or craftsmen. When they arrive at the hospital, these injured people are placed on a stretcher and entrusted to the care of a nurse or an intern who performs first aid before calling the physician on duty. When it comes to road victims, a kind of fatalism prevails in society.

"Let's take the medical art from the foot of the tree to the operating theatre”

Louis Serre was one of the first to speak out against these undeserved deaths, this unjust pain and this medical wait-and-see attitude in hospitals. He saw his father, a physician in the Cévennes, go out day and night to assist in childbirth, to give a few life-saving pills to a breathless heart patient, to reduce a fracture, to inject morphine into a patient at the end of their life. And he, the hospital resuscitator, is forced to wait in the hospital to provide care and alleviate suffering until it’s late, often too late. This is unbearable for him. He took the initiative of organising a meeting in the spring of 1966 in Dr. Bourret's office at the hospital in Salon-de-Provence, a hotbed of seasonal road migration.2 Louis Lareng, an anaesthetist from Toulouse, was invited. It was at this meeting that Louis Serre put forward the innovative idea of "medicalising" road accident victims, in the same way that the transport of poliomyelitis patients had been "medicalised". Everyone approved.

Louis Serre then had this founding phrase: "Let's take the medical art from the foot of the tree to the operating theatre”. With these few words, which have now passed into posterity, he defined a revolutionary concept, that of taking the physician out of the hospital to provide care at the very site of the accident and then accompany the victim to the place of optimal treatment.

A little corner of the vestry...

It remains to put this generous idea into practice. One of the first difficulties was to convince the other hospital colleagues who, out of habit or perhaps because they regretted not having initiated this project themselves, were initially opposed to physicians leaving the hospital to work in the countryside or the suburbs.

Even to find available premises, Louis Serre had to fight. This was so true that only the chaplain of the Saint-Eloi hospital offered a corner of the vestry to house the first physicians on duty. It seems, but this is surely gossip, that since the nights were long and the guards were mixed, certain approaches were made discreetly, despite the sacred nature of the premises. If this is true, the god of emergencies did not seem to mind too much.

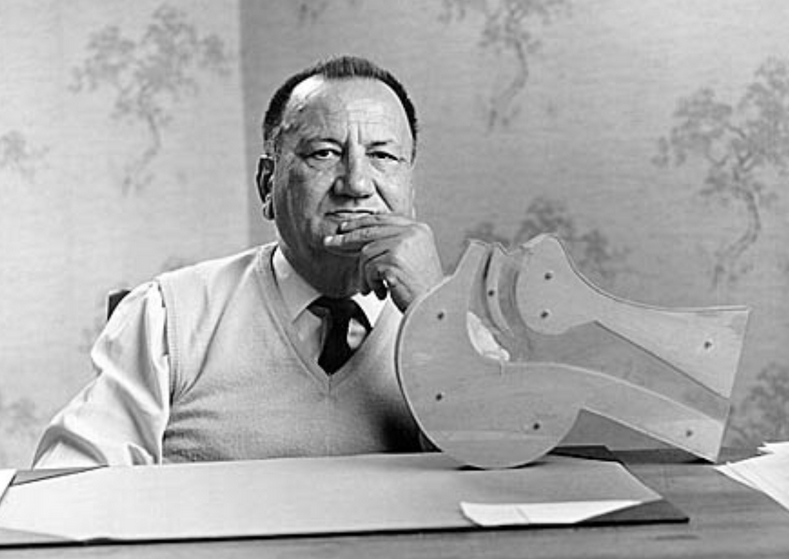

Louis Serre's enthusiasm, his strength of conviction and the soundness of his ideas eventually won over the most grumpy of people. Those who knew "Louis", as he wished to be called, this man who was as simple as he was generous, remembered him for his uncommon qualities as a teacher and his luminous clinical sense. He taught emergency medicine as the Greek philosophers spoke on the agora.3 Everything seemed simple with him. On his desk was a simplified model showing how to free the upper airway with a single movement and avoid asphyxia, the leading cause of death for comatose patients.

To ensure that these medical ambulances were really available to the whole population, Louis Serre succeeded in getting the health authorities to create a special, easily remembered number. This was the famous 72.00.00. It predated the "15", later adopted by the SAMU, of which Louis Serre remains historically the first "boss". In his mind, moreover, the acronym "SAMU" did not mean Emergency Medical Assistance Service but Emergency Medical Assistance System (French: Service/Système d’aide médicale urgent). From the outset, he wanted to include local general practitioners in this organisation who, after specific training, could also intervene before the arrival of a hospital specialist. Louis Serre had not forgotten the role of these physicians who, like his father, knew how to make themselves available to their patients. Activated by the same call number as the hospital SMUR (Services mobiles d’urgences et de reanimation, Mobile Emergency and Resuscitation Service), these physicians became even more efficient, becoming part of a fully integrated medical service, from isolated locations to the hospital.

This is how Montpellier became the first city in France to have a coherent pre-hospital emergency medical service, operational 24 hours a day. Toulouse followed closely behind. These two fully active services demonstrated, on a daily basis, the soundness of the concept and the advantages of moving physicians closer to the victim. What seemed to be common sense was thus scientifically proven. Lives were saved by specialised medical procedures carried out at an early stage. But also, and this was a substantial improvement, traumatised and fractured people benefited from infinitely less painful transport thanks to the injection of powerful analgesics.

The first SMUR vehicles (credits: DR)

Their usefulness for accident victims having been demonstrated, these new "physicians outside the walls" were also, quite logically, sent to patients suffering from acute medical pathologies, cardiac or otherwise. Here again, with the same beneficial results. The way was open for a salutary generalisation of the system.

Louis Serre was also a pioneer in the use of rescue helicopters. The first machines in his department were loaned by the French Army Aviation (Aviation légère de l’armée de terre, ALAT). They made it possible to reach victims in isolated and remote places, and thus to offer an idea close to Louis’ heart, "equality of opportunity to all in all parts of the country".

Louis, the "father" of all medical professionals who go where they are needed, has been resting since 11 November 1998 in the small cemetery of Saint-Laurent-le-Minier, in the heart of a Cévennes region so dear to his heart. Some old "emergency physicians", aware of what they owe him, sometimes pass by to say hello.

References:

1. Doctor I'm afraid! (Original title: Docteur j’ai peur!, 2017) and From one continent to another - of tears and hope (Original title: D'un continent, l'autre - de larmes et d'espoir, 2020).

2. Salon-de-Provence is located at the crossroads of the N7 from Paris and the Italy-Spain axis.

3. Public square where the Greeks debated.

* About Prof. Nicolas Peschanski

Prof. Peschanski is a professor of emergency medicine and a hospital practitioner at the University Hospital of Rennes. He has been an active member of the SFMU (Société Française de Médecine d’Urgence, French Association for Emergency Medicine) for many years - with six years spent on the scientific committee - and has been a member of the referentials committee since 2020. Professor Peschanski's international career, particularly in the USA, has enabled him to become a member of the International Commission of the American College of Emergency Physicians as well as the leading committee of the EMCREG-International (Emergency Medicine Cardiac Research and Education Group). He is also a member of the European Society for Emergency Medicine (Eusem) and particularly of its "Web & Social Media" committee. Peschanski is very attached to the FOAMed principle (Free Open Access Meducation). He uses social networks (@DocNikko) for educational and knowledge sharing purposes in emergency medicine.